After last Sunday’s record-setting storm in Southern California, and the cool, unsettled weather during the week, we expected snow conditions on Mt. San Jacinto to be even better than on previous trips this March. But snow conditions — especially backcountry snow conditions — aren’t always what you expect. The new snow, maybe a foot of it, was as thick as wet concrete. If we’d had a little kiwi fruit flavoring, it would have been perfect for shave ice.

Even if the snow wasn’t what we had hoped for, the day was extraordinary. Another weak front was moving into Southern California and the strong onshore flow ahead of the front was creating several kinds of interesting mountain weather phenomena — some common and some not so common.

Riding up the tram, we could see plumes of dust blowing across the desert floor east of Banning Pass, and a stack of lenticular clouds hovered over the mountains east of San Gorgonio Mountain. It was breezy at the upper tram station, and from the walkway descending to Long Valley, we could see rimed trees on the southeast side of San Jacinto Peak.

We skied up a beautiful untracked drainage south of the Round Valley trail, and eventually worked our way over to Long Valley Creek and then to Tamarack Valley. We were almost to the top of the steep step above Tamarack Valley, and had paused for a moment to look around. There was a distinctive wave cloud to the southeast, and the lower cloud deck was beginning to engulf Toro Peak (8716′). I turned to continue up the slope, and as I looked up, the first of a series of tumbling and twining filaments of gossamer cloud swept past in the turbulent west-northwest flow (video).

Six months ago, also before the passage of a cold front, I’d seen similar clouds on Boney Mountain, in the Santa Monica Mountains. In that case and here on San Jacinto, a moist layer in a stably stratified westerly flow was being lifted over a mountain range. Depending on whether the flow remained laminar, or became transitional or turbulent; a wave cloud, transient wave cloud, or these turbulent thin sheets of cloud might form. In each case the atmosphere was becoming more moist and the clouds were precursors to the formation of a more widespread and persistent cloud layer.

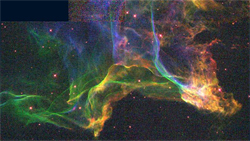

These vaporous, turbulence-induced clouds bear a striking resemblance to interstellar molecular clouds. Both appear to occur in a high-Reynolds-number regime, and each appears to consist of a cohesive, thin sheet of condensate that can be stretched, sheared, undulated and torn. As in the case of its interstellar counterpart, when viewed edgewise, the clouds look like they are comprised of thin, web-like filaments.

The title photo was taken a little below the summit, after ascending the peak. It’s a view to the south, past Jean Peak (10,670′) and Marion Mountain (10,362′), and shows the terrain induced uplift, waves, and turbulence over the San Jacinto mountain range. The flow is from the right to left.