From Sunday’s run to Mt. Abel and back from Mt. Pinos in Los Padres National Forest.

From Sunday’s run to Mt. Abel and back from Mt. Pinos in Los Padres National Forest.

From a run at Ahmanson Ranch (now Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve).

Update. The Mt. Hawkins lightning tree lost it’s crown over the Winter of 2019-2020.

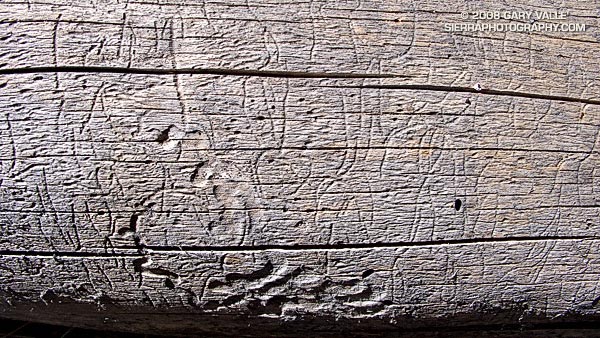

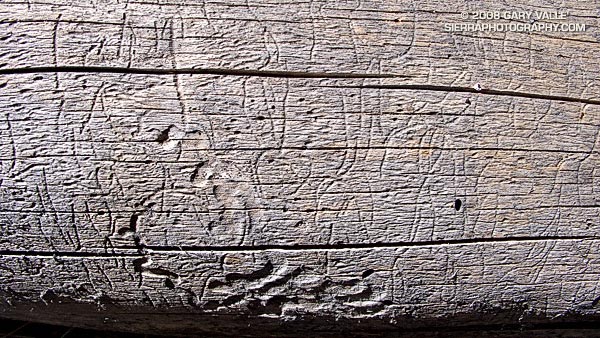

An unusual, offset lightning scar on a Jeffrey pine in the San Gabriel Mountains, near Los Angeles. The tree is located at an elevation of about 8750′, on the ridge east of Mt. Hawkins.

The offset scar is not easily explained. Either the scar was offset when created, became offset as the tree aged, or perhaps multiple strikes have somehow created the appearance of an offset. None of these explanations seem completely satisfactory.

The lightning scar on the Mt. Hawkins tree appears to be older than the scar on the Jeffrey pine on the Three Points – Twin Peaks Saddle trail, and quite a bit older than the scar on the Jeffrey pine on Mt. Baldy’s North Backbone Trail.

Or did the Curve Fire trigger a lightning strike?

These trees — on a section of the Pacific Crest Trail east of Windy Gap — were burned almost six years ago in the 20,857 acre Curve Fire. According to the Curve Fire Burned Area Emergency Report Implementation Plan, the source of ignition for the devastating fire was “a ritual involving the use of fire (candles) and animal sacrifices.” The fire started the afternoon of September 1, 2002.

However, in the document An Exercise Involving Flash Flood and Lightning Potential Forecasts, an alternative ignition source was suggested — an “out of the blue” lightning strike. Forecasters observed a “single positive lightning strike northeast of the Mount Wilson Observatory” about 1:00 PM PDT (2000Z), near the time the Curve Fire started. According to NWS Lightning Safety Outdoors, such bolts from the blue have been documented to travel more than 25 miles from a thunderstorm cloud.

While there is compelling evidence that the blue sky lightning strike occurred, the time of the strike suggests that it was not the initial source of ignition of the Curve Fire. This UCLA Solar Towercam image is time-stamped at 12:58:58, about the time of the strike. It shows the Curve Fire already underway, with a well-developed smoke column. The photograph also shows the cloud development over the San Gabriel Mountains.

An intriguing question comes to mind. Was the lightning strike a coincidence, or was it somehow triggered by the fire, or the smoke?

According to “Forest Fires: Behavior and Ecological Effects” by Edward A. Johnson, Kiyoko Miyanishi (Academic Press, 2001) large scale lightning detection networks have revealed an association between forest fires and the electrification of thunderstorms. Further, “a shift from negative to positive ground flash prevalence in association with fires and forest fire smoke” has been documented.

So it looks like lightning did not start the Curve Fire, but the Curve Fire may have triggered the positive lightning strike observed by the NWS!

The photograph of trees burned in the Curve Fire is from Sunday’s Islip Saddle – Mt. Baden-Powell South Fork run.

Related post: Explosive Growth of the Lake Fire

Technical papers:

CLOUD-TO-GROUND LIGHTNING DOWNWIND OF THE 2002 HAYMAN FOREST FIRE IN COLORADO

Timothy J. Lang* and Steven A. Rutledge

Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado

Enhanced Positive Cloud-to-Ground Lightning in Thunderstorms Ingesting Smoke from Fires

Walter A. Lyons, Thomas E. Nelson, Earle R. Williams, John A. Cramer, and Tommy R. Turner

Science 2 October 1998 282: 77-80 [DOI: 10.1126/science.282.5386.77] (in Reports)

Incense cedar on the Burkhart Trail in Cooper Canyon. From Sunday’s Three Points loop.

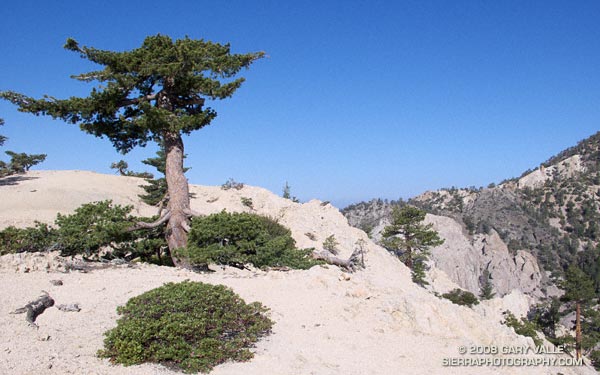

Often described as the largest and tallest of the pines, Sugar pine can grow to heights of 150 feet or more. According to the National Register of Big Trees, the current U.S. champion sugar pine measures 209 ft. tall, with a spread of 59 ft.

The sugar pine pictured above is only a fraction of this size — at first glance it looks like the tree has been topped. Its reduced height is due to the harsh environment in which it grows. Sugar pine and Jeffrey pine found on the higher windswept ridges and mountain tops of the San Gabriel Mountains (and other ranges) are often stunted in this manner.

Research suggests that a number of factors contribute to this adaptation. Foremost among these factors is wind. A tree will respond to a windy environment by increasing the diameter of its trunk, and reducing its height. Water stress is another key factor. Shallow granular soil, low humidity, increased radiation, hot summers and cold winters increase water stress; and a windy environment will amplify the stress.

In such a demanding environment everything matters — snow deposition patterns, aerodynamic effects, competition with brush, subtle differences in slope aspect, mechanical damage, damage from pests, and more.

The photograph of the sugar pine is from the Pleasant View Ridge Snow run in May.