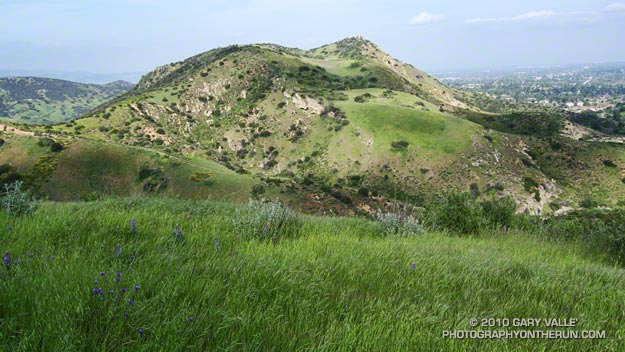

Castle Peak from a trail near the northern boundary of Ahmanson Ranch, west of El Scorpion Park.

From today’s 8.5 mile circuit around Ahmanson Ranch.

Castle Peak from a trail near the northern boundary of Ahmanson Ranch, west of El Scorpion Park.

From today’s 8.5 mile circuit around Ahmanson Ranch.

This time of year if you’re running in Southern California’s canyons and notice a subtle, pleasantly pungent, and slightly sweet fragrance wafting about the area, look around, poison oak is probably near.

The small, greenish, five-petaled blossoms generally hide under the “leaves of three” and are easy to miss.

From today’s run in the Simi Hills.

Related post: Poison Oak

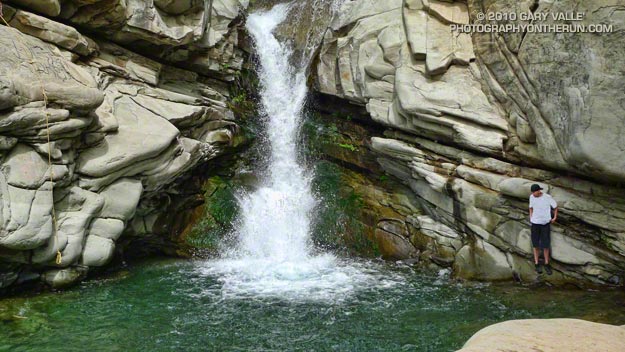

No doubt about it, waterfalls have a special attraction. Angel Falls, Niagara Falls, Victoria Falls, Yosemite Falls — people travel the world and spend thousands to see them.

They are the five star hikes in guidebooks, and THE iconic image of the outdoors. They are so compelling that I have been running on a trail along a dry creek, on a 100 degree summer day, when it hasn’t rained for months, and been asked, “How far is it to the waterfall?”

To be an attraction they need not be big, spectacular, or even flowing. One of the most popular hikes in the Santa Monica Mountains is the mile-plus hike from Temescal Gateway Park to the ephemeral 10 ft. cascades of Temescal Canyon Falls.

Waterfalls must tweak our aesthetic being in such a way we just can’t resist. If you spend much time in the outdoors, or even if you don’t, you’ve probably done at least one hike to see a waterfall.

Here’s a California State Park Press Release from 2006 listing some waterfalls in, or near, California’s State Parks.

Paddled Limestone on the Upper Kern today. The flow on the Upper was about 1000 cfs, midday temps were around 70, and the water a balmy 40-something. Given the good Spring flow and weather, we were surprised no other paddlers were on this section of the river.

The drive between Kernville and the San Joaquin Valley was exceptionally scenic. Kern Canyon’s steep slopes were as green as they get.

Even if the calendar is a little slow, Spring is here. The oaks are leafing out, goldfields blooming, chorus frogs singing, and I just had my first rattlesnake encounter of the year.

The single track trail paralleled the dirt road in upper Las Virgenes Canyon. I weaved and wound my way through the grassland and oaks, eventually returning to the road near the connector to Cheeseboro Canyon.

Usually, the sound of my footfalls would be enough to abruptly silence the sing-song of the frogs at the creek crossing. As I approached the creek, the calls slowed but did not stop. I paused at a small pool and stood quietly.

Over a period of seconds, the chorus of the frogs grew to a surprising intensity, interleaving and reverberating in such a way as to envelop me in sound. In the small pond at my feet, I could not see the frogs, but I could see the waves and ripples of their calls on the water’s surface. Immersed in sound, I stood still for a few moments, and then crossed the creek, and continued down the canyon.

I’d been thinking about it earlier in the run. Highs had been in the 80’s since Monday. Was three days enough to get the rattlesnakes out and about?

I reacted to the rattle before I heard it, leaping away from the sound. The snake was in the grass at the margin of the trail, about halfway up “the Beast,” west of Lasky Mesa. It was nearly invisible in the tall grass, and only an inch or two off the overgrown path. Fortunately, it’s reaction had been similar to mine, a defensive recoil, rather than a strike.

The adrenalin of the encounter quickened my pace up the hill. At the top of a hill, a falcon flew from a sentinel oak. I followed its flight until it disappeared in the glare of the setting sun, and sighed…

Because of their unusual “flying saucer” appearance, lens shaped lenticular clouds have long drawn attention. According to a research article in Weather, depictions of wave clouds appear in Gothic art from the 15th century.

Lenticular clouds typically form when wind flows into, and then up and over a mountain range, creating a series of “roller coaster” atmospheric waves downwind of the range. Lenticular clouds can (but don’t always) form in the peaks of the waves, as a layer of air rides up a wave, and cools and condenses. The waves are called standing waves because the peaks and troughs can stay (more or less) in the same place for hours at a time.

The rising air on the windward side of a lee wave can be soared by gliders to high altitudes. According to the FAI, the current world absolute altitude record for gliders is 15,460 meters (50,722 ft.). This record was set by the late Steve Fossett in 2006, soaring a mountain wave in the Andes. Mountain wave soaring was pioneered on the east side of the Sierra, and several single place sailplane world altitude records have been set soaring the Sierra wave.

Lee waves also have a nefarious side. Rotors, breaking waves, and other phenomena associated with mountain waves can create extreme turbulence. A sailplane destroyed in early research on rotors was estimated to have experienced 16 g of acceleration. According to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, “clear air turbulence associated with a mountain wave ripped apart a BOAC Boeing 707 while it flew near Mt. Fuji in Japan. In 1968, a Fairchild F-27B lost parts of its wings and empennage, and in 1992 a Douglas DC-8 lost an engine and wingtip in mountain wave encounters.”

The wave clouds above were photographed northwest of Los Angeles during a trail run earlier this month. The wind forming the wave clouds appears to be from the north-northeast. The situation was peculiar because the wind at nearly all levels at that time was from the northwest. The tops of the wave clouds are being sheared by winds blowing from the northwest (left to right).

Here’s an animated series of NRL satellite photos showing the waves pictured above, and the complex wind and wave pattern at the time of the photograph.