From another excursion up and over Kearsarge Pass.

From another excursion up and over Kearsarge Pass.

Poised on a glacial bench a dozen miles west, and few thousand feet above Independence, California, Onion Valley is the starting point for many a Sierra adventure. Kearsarge Pass provides relatively quick and easy access to the heart of the Sierra, and the more technical passes south and north of Kearsarge can be used by mountaineers to access peaks along the crest, or basins on the west side of the crest.

It is an area that is dramatically alpine, and I have returned again and again to climb peaks such as Independence Peak and University Peak and to hike, run and explore. One Summer Phil Warrender and I did a trans-Sierra hike that started here and took us over University Pass, Andy’s Foot Pass (13,600′), Milly’s Foot Pass, Longley Pass and Sphinx Pass, ending at Cedar Grove. We went superlight (about 15 lb. packs w/o ice axe), did as much cross-county as possible, and climbed a few peaks along the way.

Today Miklos, Krisztina and I were doing a reconnaissance hike/run up and over Kearsarge Pass, and down into the Kearsarge – Bullfrog – Charlotte Lakes basin, and back. The idea was to pick a time when the Kearsarge Pass trail would be mostly free of snow, but when much of the surrounding terrain would still be accented in white.

What a day! Perfect temps, little wind, excellent trail conditions, super scenery, and absolutely outstanding trail running.

Here are a few photographs:

Big Pothole Lake from the east side of Kearsarge Pass. Nameless Pyramid (right) and University Peak (left) on the skyline.

View west from Kearsarge Pass over Kearsarge Lakes and Pinnacles to Mt. Brewer (left), North Guard (middle) and Mt. Francis Farquhar (right) on the skyline.

Kearsarge Lakes and Pinnacles from the north.

Miklos and Krisztina above Bullfrog Lake. East Vidette is the prominent conic peak. Deerhorn Mountain is at the head of the recess to the right of East Vidette.

Scrambling above the John Muir Trail about a mile from Glen Pass. Charlotte Dome is in the distance.

Here’s a Google Earth image and a Google Earth KMZ file of a GPS trace of our route.

Bumblebee on Kotolo milkweed. From a run on Lasky Mesa in Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve (formerly Ahmanson Ranch).

Was that a snake on the trail ahead?

It was a snake — a pretty big one — stretched across two-thirds of the road.

I slow, stop running, and then walk carefully toward it. The snake is dead still. A confounding series of thoughts follow in quick succession.

Looks like it’s probably a gopher snake… Glance at the tail — no rattles. Check the head — where’s the head? Check the tail again — definitely no rattles. It is a gopher snake. Look for the head again — did the snake get run over, or decapitated?

At least 30 seconds have passed and the snake has not moved — not a millimeter. Very weird. Is it dead? It doesn’t look dead. There’s no blood.

Realization dawns as I comprehend the snake may be caught in the entrance to a small burrow.

Com’on, stuck? If so, it’s in a bad place. Pick your peril: Upper Las Virgenes Canyon is hiked, biked, ridden on horseback, roamed by coyotes, and hunted by hawks.

Now it’s been a couple of minutes, and the snake still has not moved. I’m beginning to think maybe it is dead. So I touch it.

Panic! The snake writhes, contorts and convulses in an attempt to free itself. No go — it continues to convulse, and then suddenly, and impossibly, slithers down the hole.

What? My guess is that the snake had found a lizard, mouse, or other prey in the hole, started to swallow it, and with its body engorged, became trapped by its meal. Or maybe it just got stuck!

Prickly poppy (Argemone munita) in upper Cheeseboro Canyon.

From today’s run of the Cheeseboro Canyon keyhole loop, starting from the Victory trailhead of Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve (formerly Ahmanson Ranch).

Here’s a Google Earth image of a GPS trace of the loop, and links to trail maps for Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve and Cheeseboro/Palo Comado Canyons.

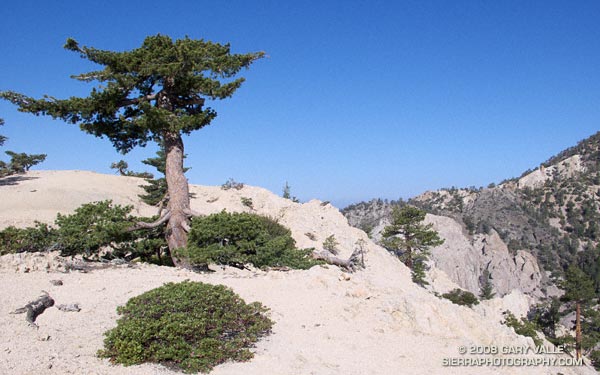

Often described as the largest and tallest of the pines, Sugar pine can grow to heights of 150 feet or more. According to the National Register of Big Trees, the current U.S. champion sugar pine measures 209 ft. tall, with a spread of 59 ft.

The sugar pine pictured above is only a fraction of this size — at first glance it looks like the tree has been topped. Its reduced height is due to the harsh environment in which it grows. Sugar pine and Jeffrey pine found on the higher windswept ridges and mountain tops of the San Gabriel Mountains (and other ranges) are often stunted in this manner.

Research suggests that a number of factors contribute to this adaptation. Foremost among these factors is wind. A tree will respond to a windy environment by increasing the diameter of its trunk, and reducing its height. Water stress is another key factor. Shallow granular soil, low humidity, increased radiation, hot summers and cold winters increase water stress; and a windy environment will amplify the stress.

In such a demanding environment everything matters — snow deposition patterns, aerodynamic effects, competition with brush, subtle differences in slope aspect, mechanical damage, damage from pests, and more.

The photograph of the sugar pine is from the Pleasant View Ridge Snow run in May.