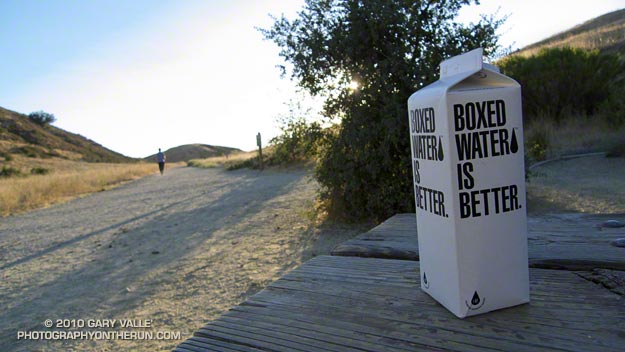

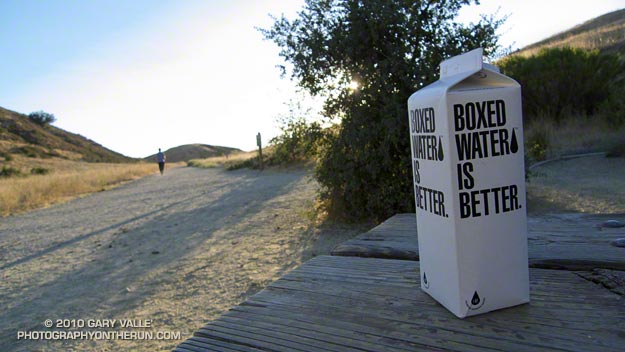

…Or maybe tap water in a reusable container?

Here’s more info about Boxed Water is Better.

From today’s run at Ahmanson Ranch.

…Or maybe tap water in a reusable container?

Here’s more info about Boxed Water is Better.

From today’s run at Ahmanson Ranch.

Study of the leaflets of a tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima).

An invasive plant introduced from China, Ailanthus is very common along the Kern River. It appears to be well-adapted to growing in the cobble along stream banks. It spreads through root sprouting and seeds, producing thickets which displace native vegetation.

According to Wikipedia, the tree of heaven “Was mentioned in the oldest extant Chinese dictionary and listed in countless Chinese medical texts for its purported ability to cure ailments ranging from mental illness to baldness.”

Originally posted 5/27/07. Previously updated 9/15/10. Scoping letter info added 12/22/13. Draft EIS info added 8/21/18.

Update 8/21/18. Nearly 13 years after the closure of Williamson Rock and a key segment of the Pacific Crest Trail, the Forest Service has released a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Williamson Rock Project. The public comment period is from July 27 to September 10, 2018. For additional information see the Forest Service Williamson Rock Project page and the Access Fund page REOPEN WILLIAMSON ROCK TO CLIMBING!

Update 12/22/13. New Williamson Rock/PCT scoping letter, dated 12/18/13, from Angeles National Forest to “consider resuming recreation opportunities in the currently closed area, in and around Williamson Rock.”

————

Located in Angeles National Forest (ANF), Williamson Rock is an area of exceptional scenic and recreational value. Because of its proximity to Los Angeles, variety of climbing routes, scenic beauty, and moderate summertime temperatures, it is one of the most popular rock climbing areas in Southern California.

In December 2005, in order to protect critical habitat of the mountain yellow-legged frog (MYLF), the Forest Service “temporarily” closed approximately 1,000 acres in the upper Little Rock Creek drainage in the San Gabriel Mountains. The closed area includes Williamson Rock, and the Pacific Crest Trail between Eagle’s Roost and the Burkhart Trail.

In May 2007 the Forest Service issued a press release and scoping letter proposing an access trail and initiating an environmental analysis. Now, nearly five years after the “temporary” closure of Williamson Rock, and following many delays, Angeles National Forest has completed a draft Environmental Assessment (EA) whose bottom line recommendation is to extend the closure another three years!

In the draft EA, the Forest Service says the extension is needed,”while neighboring [MYLF] population segments are given time to rebound from the effects of wildfire and consequent watershed emergency.”

The Forest Service’s recommendation to extend the closure is based on a false premise, that closure of MYLF habitat, and adjacent land, will protect the MYLF population. There is substantial evidence that this is not the case. This was recognized in the 1999 paper (Mahony, et al.) in which researchers assessed the disappearances and declines among Australian frogs and proposed methods to prevent further losses:

“It is generally accepted that the least expensive way of preventing extinction and loss of biodiversity is the maintenance of habitats. This argument is well established in the conservation biology literature (Caughley and Gunn 1996), however, it does not consider or deal with a situation such as that which currently faces frogs in Australia and globally. One of the puzzling features is that species have disappeared from areas of pristine or near pristine habitat and areas of large reserves where there are no indications of habitat destruction. Similarly, there is no evidence that an introduced competitor or predator is responsible, apart from the hypothesis that an introduced pathogen is involved (Laurance et al. 1996). Preservation of habitat or declarations of new reserves would not have halted or prevented the loss of the majority of species.”

Since this paper was published, there has been much research in this area, and there is a growing body of evidence that global declines in many species of frogs, including the MYLF, is due to infection from the chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd).

It is believed that the fungus is spread through its own movement in water, the flow of water, and by the activity of infected amphibians. Because infection has occurred in pristine, widely separated populations, it is hypothesized that other vectors, such as birds, fish, animals or insects, could play an important role in its spread. Research has shown that spread by birds and other mechanisms are a possibility (Johnson & Speare, 2005). It is also a possibility that Bd has been present in amphibian populations worldwide for some time (Rachowicz et al., 2006).

In support of its recommendation that the Williamson closure should be extended, the EA states, “Indirect impacts to the frogs include the spread of pathogens, such as chytrid fungus, inadvertently carried into the habitat by visitors.”

I have found no published evidence that recreational activities, such as rock climbing, are the proximate cause of the spread of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis into MYLF habitat. It would seem especially unlikely in the context of rock climbing in usually warm and dry Southern California. Desiccation kills the fungus. In the 2005 study by Johnson & Speare, in which zoospores and zoosporangia were introduced on feathers, under most circumstances the fungus became inviable after 2 hours of drying.

According to the EA, all remaining units of the Southern California distinct vertebrate population segment (DPS) of the MYLF have already been confirmed positive for presence of Bd. This suggests that a frog unaffected by Bd is much more likely to be infected by natural mechanisms and vectors from within the infected population rather than by Bd brought into the habitat by a human visitor.

Under the EA’s Alternative 3 (The Recreational Development Alternative), in which climbers would be routed away from MYLF habitat, the probability of climbers spreading Bd from outside the habitat, or physically harming the frogs, or disrupting their habitat, would appear to be almost nil.

Rather than extending an unnecessarily prohibitive closure that is unlikely to benefit the MYLF, a plan such as Alternative 3 (The Recreational Development Alternative) should be adopted, and Williamson Rock reopened to climbing.

—

The efforts of the climbing community are being coordinated by the Friends of Williamson Rock in partnership with the Access Fund and the Allied Climbers of San Diego. The Access Fund is a national, non-profit climbers’ organization dedicated to preserving the natural resources used by climbers, and climbers’ access to those resources.

Comments regarding the draft EA, and the recommendation to extend the closure of Williamson Rock for another three years, must be submitted by October 1, 2010. Send to:

Darrell Vance

Attn: Williamson Rock Environmental Assessment

701 N. Santa Anita Ave.

Arcadia, CA 91006

Email: dvance@fs.fed.us

For more information, see the Access Fund Williamson Rock page.

The photograph of Williamson Rock was taken on the PCT while doing the run Pleasant View Ridge on July 2, 2006.

Related post: Complications

Today at 12:15 p.m. PDT the temperature at Downtown Los Angeles (USC) reached 113°F (45°C), which is the highest temperature recorded downtown since weather recordkeeping began in 1877.

It wasn’t quite as hot in the San Fernando Valley. The high temperature at Pierce College reached 110°F.

When I started my run at Ahmanson Ranch it was 106°F. I took two bottles with ice water. One was used to keep my arms, legs and head/neck wet. With the relative humidity low, this was very effective for cooling. I picked a 45-50 minute course that was not too strenuous, and kept the pace moderate.

It was a surprisingly moderate run, but I sure wouldn’t want to run out of water or have some other problem when the temperature is that high!

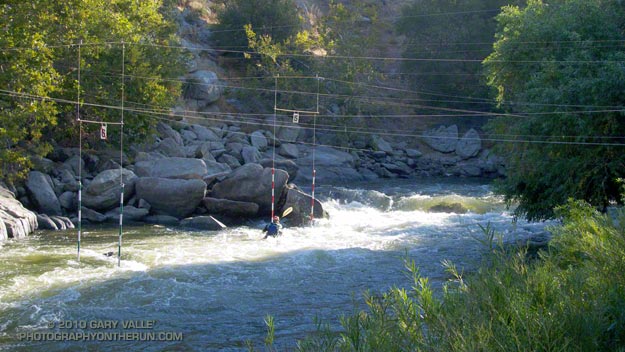

The high at Isabella Dam reached 102°F, but it was cool along the Kern River for the 2010 edition of the Miracle Whitewater Slalom Race.

Thanks to the efforts of firefighters, the Canyon Fire had been 100% contained the previous weekend, and did not burn Hobo Campground or Miracle Hot Springs, where the slalom course is located.

Last Winter’s big snowpack extended the season on both the Upper Kern and Lower Kern, and this year we were able to schedule the race in the Fall and still have excellent whitewater. Race day the flow came up to 890 cfs, a very good level for so late in the year.

The course was set so that no individual move was super difficult, but it was challenging to do the combined gate sequences well. Saturday, Olympic Silver Medalist Rebecca Giddens gave a pre-race clinic that helped paddlers deal with the difficulties of the course.

Thanks to everyone that paddled and helped with the race! Results will be posted on the KVRC web site soon.

Course description:

Gates #1 and #2 were downs in the wave train at the top of Hobo Rapid. They led to gate #3 — a flushing up in small eddy on river left at the island. A peel-out to a down in the current, gate #4, was followed by a cross-current move behind the pour-over hole to an up, gate #5, at the base of the drop on river right. A tight turn out of gate #5 was required to setup gate #6, a dive gate that wanted to eddy-out your boat. This was followed by another up, gate #7, in a good eddy on river right. Next was a series of moderate offsets, gates #8, #9, #10, ending at the top of a small rapid. Gate #11, a down just below the drop, setup a move to river left through some turbulent water and a couple of rocks to an up, gate #12.

The move from gate #12, across several current differentials to the tight down at gate #13, was one of the trickiest on the course, and there were a couple of 50’s here. Gate #13 was followed by another down, which was offset from a dive gate on river left, gate #15. The dive gate was the lead-in to a nice left-to-right “S” at gate #16. Although it was in “easy” water, the next gate on river right, gate #17, was another up that was difficult to do well. Gate #18, a down, was the last gate.

Mt. Baldy from the North Backbone Trail

If you have a passion for the outdoors, you can get pretty creative when devising a reason for doing a particular run, hike, climb, ride, paddle or other adventure. My rationale for today’s outing was that I “wanted to measure a tree.”

The tree is an isolated and aged Sierra juniper poised on a rocky ridge on the North Backbone Trail on the back side of Mt. Baldy. I’d noticed it while doing the North Backbone Trail in 2006. At that time I had estimated the girth of the tree from a photograph, using my cap for scale. I’ve been intending to get back to the tree for years, and hopefully that was going to happen today.

With one little twist. This time, instead of approaching the tree from the Blue Ridge trailhead on the back side of Baldy, I was going to start at Manker Flat, climb up Baldy, and then descend the North Backbone Trail to the tree. This meant I would get to climb Mt. Baldy twice.

It made sense to me. Labor Day weekend I had opted to do a run in the Sierra instead of the Mt. Baldy Run to the Top race. This way I could get in a good shot of elevation gain on Mt. Baldy, enjoy the wildness of the North Backbone Trail, and also measure the circumference of the Pine Mountain juniper.

Step one was to get to the top of Baldy. Instead of following the more circuitous seven mile route of the “Run to the Top” course, I took the most direct route to Baldy’s summit — the Ski Hut trail. This trail reaches the summit in a little over four miles, gaining about 3800′ of elevation along the way. It’s a rough, no nonsense trail that in its upper reaches has a wonderful high mountain character.

I was a little late getting to the trailhead, and started running up San Antonio Falls Road about 8:30. A little less than a mile from Manker I turned off onto the Ski Hut trail and started chugging upward.

What is it about a trail to the top of a peak that makes you want to push the pace? Even before I noticed the hiker below me, I was pushing it. I ran in the few places I could, but the trail was unrelenting. Was he going to catch me?

In retrospect, I might as well have stopped to pick gooseberries. I was trying to stay ahead of a runner who had averaged 5:40 minute miles on a championship cross-country course.

Hayk caught me just below the ski hut. From there to the summit we talked about running, racing, mountains and more. He had recently run a couple of marathons, and was interested in getting into ultrarunning. Even after slowing to my pace for the last two miles, his time to the summit from Manker Flat was a speedy 1:26.

It was clear above the haze in the valleys and low clouds along the coast. From Mt. Baldy’s summit, all of Southern California’s high points could be seen. To the east were the mountains of the San Gorgonio group and San Jacinto Peak; to the south Santiago Peak; and to the northwest an array of peaks in the San Gabriel mountains, including Mt. Wilson, Strawberry Peak, Twin Peaks, Mt. Waterman and Mt. Baden-Powell.

After spending a few minutes proselytizing about the great running in the surrounding mountains, I shook hands with Hayk and started jogging down the North Backbone Trail. Step two in this adventure was to get down to the tree.

After all the uphill on the Ski Hut trail, the first few yards of downhill felt pretty good. But as the trail started to plunge down Baldy’s north face, it became all too clear that THIS downhill came at a high price. Every stride down was going cost at least a couple of steep steps up on the way back.

Then there was the uphill on the downhill. The North Backbone isn’t a uniform, well behaved ridge. It has ups and downs. Big ups and downs named Dawson Peak and Pine Mountain. Just descending to the tree would require 1200′ of elevation gain, and there would be much more than that returning to Baldy.

I tried not to think about it. There was just too much to see and enjoy. The area’s complex geology had produced dramatic ridges, mile deep canyons, and 9000′-10,000′ peaks. There were windswept Jeffrey pines and gnarled and twisted lodgepoles. Rabbitbrush bloomed in profusion, its bright yellow flowers contrasting sharply with the greens of the manzanita. Here and there red daubs of paintbrush accented the sparkling tiles of gray-green Pelona schist.

It was a spectacular place to be. After doing the North Backbone Trail for the first time in 2006, I came back the following weekend and did it again. It’s that kind of place — wild, scenic and adventurous.

How far down was that (dang) tree? I’d left the summit of Pine Mountain some time ago, and was still going down, down, down. The lodgepole pine forest on my right had the right look, but the slope to my left wasn’t steep enough. Maybe just down this hill… Is it at this little saddle? Just down the ridge a little more…

Epilogue: The circumference of the juniper measured 14′ 6.5″ or about 174.5 inches. See the post Pine Mountain Juniper for more info about the tree.

Some related posts: Mt. Baldy North Backbone Trail, North Backbone Trail Revisited