Lemon lilies and sneezeweed accent this lush mountain meadow on the south side of Waterman Mountain in the San Gabriel Mountains. From Sunday’s Three Points loop, just before it started to rain.

Lemon lilies and sneezeweed accent this lush mountain meadow on the south side of Waterman Mountain in the San Gabriel Mountains. From Sunday’s Three Points loop, just before it started to rain.

If you spend much time in the mountains, sooner or later you’re going to get caught in a severe thunderstorm. I don’t mean you’re going to hear a little thunder and get a little wet. I mean you’re going to find yourself in the middle of a heart-pounding, ear-splitting, ozone-smelling, sense-numbing storm that drenches you through and through and wrings the nerves from your body.

Having been caught in such thunderstorms while climbing in Yosemite, running in the San Gabriels, and running at Mt. Pinos, I do my best to avoid the beasts. Sometimes, it is not an easy thing to do.

Take this weekend for example. I have a 50K race coming up, and in addition to increasing my weekday mileage, I needed to do a Sunday run of about 20-25 miles — preferably in the mountains.

The Sierra was out. A monsoon pattern virtually assured widespread, and possibly severe, thunderstorms. Some forecast models were saying that the focus on Sunday might be the Ventura County mountains, so Mt. Pinos — the site of my most recent thunderstorm adventure — was also out. Both San Gorgonio and San Jacinto had been hit pretty hard on Saturday. That left the San Gabriels, and thunderstorm activity was expected there as well.

The choices were A — get up really early and try to beat the heat and humidity and run local; or B — get up really early and try to get in a mountain run before the weather OD’d…

Running up the Mt. Waterman Trail, one of my ever-optimistic running partners voiced, “Hey, have you heard about the unusual number of lightning deaths recently?” So far it had been a spectacular day. A broken layer of mid-level clouds — remnants of yesterday’s storms — shrouded the sky. By keeping things a little cooler, the clouds had delayed the development of today’s thunderstorms.

We had started at Three Points and run up the Pacific Crest Trail to Cloudburst Summit, then down into Cooper Canyon, where we left the PCT and ascended the Burkhart Trail to Buckhorn Campground. In Cooper Canyon it was obvious there had been heavy rain the day before. Everything was wet, and the willows and lupines along the creek glistened in the muted morning sun. Rivulets of rainwater had incised rills in the trail, pushing pine needles and other debris into patterned waves.

I had already lost the “when it would start raining” bet. I had said 11:00. It was 11:00 now, and still there was very little cloud development. So little in fact, we decided to do a quick side trip to Mt. Waterman (8038′), and jokes were being made about the rain gear in my pack. (My GoLite 3 oz shell made a huge difference in the severe thunderstorm on Mt. Pinos.)

About the time we summited Waterman, things started to cook. The canopy of protective clouds was beginning to thin and dissipate and some cumulus cells were starting to build. I wondered if we would make it back to the car before it dumped.

We didn’t. About 30 minutes later, as we worked down the back side of Mt. Waterman toward the junction with the Twin Peaks trail, we heard our first grumbling of thunder. In another 30 minutes it started to rain; slowly at first, with large icy drops, then building in intensity, as prescribed in long established thunderstorm protocols. Periodic claps of thunder echoed overhead, and to the north and east.

About 3 or 4 miles of trail remained. Here, the trail winds in and out of side-canyons and for the most part is well below the main ridge, but at some points it is very exposed. Minutes before, we had run past a lightning scarred Jeffrey Pine. Burned and blackened, the bolt had killed the tree. I pick up the pace and try to put the tree out of mind.

It rained hard for a while and then the intensity diminished. The air temperature didn’t drop and the wind wasn’t strong. It seems most of the lightning is cloud-to-cloud and away from us. I’m drenched, but happy — instead of being fierce and frightful, this thunderstorm has been almost puffy-cloud friendly.

In steady rain, we cross Hwy 2 and jog up the trail toward the Three Points parking lot (5920′). As we near our cars, we’re startled by a loud boom of thunder directly over our heads — a not so gentle reminder that thunderstorms come in all sizes, and none come with a guarantee.

Here’s a Google Earth image and Google Earth KMZ file of the loop, including the side trip to the summit of Mt. Waterman.

Some related posts: Manzanita Morning, Three Points – Mt. Waterman Loop

We were making good progress up the gargantuan north face of University Peak (13,632′), climbing carefully and doing our best not to knock loose rocks down on each other’s heads. We were also doing our best to ignore the gathering clouds — and the unnerving rumble of distant thunder.

Yes, it would have been better to sleep at the trailhead and get an early start. Especially with a 20% chance of isolated thunderstorms in the forecast. But we didn’t. When we should have been taking our first steps on the Kearsarge Pass trail we were eating breakfast burritos in Mojave. So it goes.

Now we were about half way up the 2200′ class 2-3 face, and it would take another hour of climbing to reach the summit. That would put us on the summit right around the time of maximum daytime heating — a bad time to top out if you’re trying to avoid a thunderstorm.

Off to the northwest there was another long, rolling, rumble of thunder. Streamers of rain could be seen twining from darkening clouds. Smoke from one or more of California’s many fires hung in the valleys to the west of the crest, producing an unnatural and eerie mixture of clouds, smoke, rain, and orange tinted terrain.

We paused in a jumble of broken blocks of granite, hemming and hawing, and otherwise hesitating to make THE decision to descend. Avoiding the issue and pondering the sky, we wondered which fire the smoke was coming from, and — half in jest — whether the smoke could have seeded and enhanced the thunderstorm we were watching. Those questions, it turns out, had surprising answers.

I had assumed the smoke was from one of the fires to the west. But this NRL Aqua-MODIS True Color satellite photo from 1:38 in the afternoon reveals the source of the smoke — it was from the Piute Fire between Lake Isabella and Tehachapi. The long plume of smoke from this fire feeds almost directly north into the large thunderstorm cluster near 37N and -118.5W.

From our vantage point on University Peak, the southern margin of this activity appeared to be about 6 miles away, somewhere near Gardiner Basin. This experimental NRL image shows the convection more clearly. Could this smoke plume have enhanced the storms over the Sierra?

The research article “Smoking Rain Clouds over the Amazon” by M. O. Andreae, et al, published in Science Magazine in 2004, and related research, suggests the possibility. According to that article, vegetation burning produces high concentrations of aerosols which are capable of nucleating cloud droplets. But, convective clouds forming in smoky air show substantially reduced droplet size compared to similar clouds in clean air. The reduced droplet size can delay the onset of precipitation, which in turn can result in enhanced convection.

So why blame the thunderstorm on Cristina? This NRL water vapor satellite photo from 3:30 p.m. suggests that the source of the moisture for the Sierra thunderstorms was Tropical Storm Cristina. An upper level low spinning off the coast had drawn the moisture up from the tropics and into the Sierra.

Related post: Thunderstorm, Shadow and Sun on University Peak (The north face is highlighted by the sun.)

From another excursion up and over Kearsarge Pass.

Poised on a glacial bench a dozen miles west, and few thousand feet above Independence, California, Onion Valley is the starting point for many a Sierra adventure. Kearsarge Pass provides relatively quick and easy access to the heart of the Sierra, and the more technical passes south and north of Kearsarge can be used by mountaineers to access peaks along the crest, or basins on the west side of the crest.

It is an area that is dramatically alpine, and I have returned again and again to climb peaks such as Independence Peak and University Peak and to hike, run and explore. One Summer Phil Warrender and I did a trans-Sierra hike that started here and took us over University Pass, Andy’s Foot Pass (13,600′), Milly’s Foot Pass, Longley Pass and Sphinx Pass, ending at Cedar Grove. We went superlight (about 15 lb. packs w/o ice axe), did as much cross-county as possible, and climbed a few peaks along the way.

Today Miklos, Krisztina and I were doing a reconnaissance hike/run up and over Kearsarge Pass, and down into the Kearsarge – Bullfrog – Charlotte Lakes basin, and back. The idea was to pick a time when the Kearsarge Pass trail would be mostly free of snow, but when much of the surrounding terrain would still be accented in white.

What a day! Perfect temps, little wind, excellent trail conditions, super scenery, and absolutely outstanding trail running.

Here are a few photographs:

Big Pothole Lake from the east side of Kearsarge Pass. Nameless Pyramid (right) and University Peak (left) on the skyline.

View west from Kearsarge Pass over Kearsarge Lakes and Pinnacles to Mt. Brewer (left), North Guard (middle) and Mt. Francis Farquhar (right) on the skyline.

Kearsarge Lakes and Pinnacles from the north.

Miklos and Krisztina above Bullfrog Lake. East Vidette is the prominent conic peak. Deerhorn Mountain is at the head of the recess to the right of East Vidette.

Scrambling above the John Muir Trail about a mile from Glen Pass. Charlotte Dome is in the distance.

Here’s a Google Earth image and a Google Earth KMZ file of a GPS trace of our route.

Often described as the largest and tallest of the pines, Sugar pine can grow to heights of 150 feet or more. According to the National Register of Big Trees, the current U.S. champion sugar pine measures 209 ft. tall, with a spread of 59 ft.

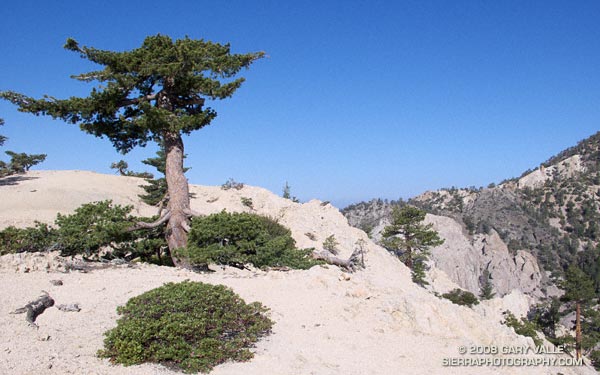

The sugar pine pictured above is only a fraction of this size — at first glance it looks like the tree has been topped. Its reduced height is due to the harsh environment in which it grows. Sugar pine and Jeffrey pine found on the higher windswept ridges and mountain tops of the San Gabriel Mountains (and other ranges) are often stunted in this manner.

Research suggests that a number of factors contribute to this adaptation. Foremost among these factors is wind. A tree will respond to a windy environment by increasing the diameter of its trunk, and reducing its height. Water stress is another key factor. Shallow granular soil, low humidity, increased radiation, hot summers and cold winters increase water stress; and a windy environment will amplify the stress.

In such a demanding environment everything matters — snow deposition patterns, aerodynamic effects, competition with brush, subtle differences in slope aspect, mechanical damage, damage from pests, and more.

The photograph of the sugar pine is from the Pleasant View Ridge Snow run in May.