Update October 2, 2024. I ran the ANFTR 25K Course on Sunday and the cuttings on the Mt. Disappointment/Bill Riley Trail had been removed. The trail was clear and back to normal!

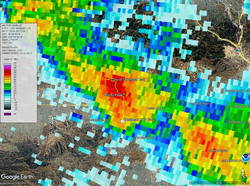

As I drove east on the 210 Freeway, a long bolt of lightning erupted from high in the clouds and pierced the valley below. The thunderstorm near Mt. Lukens looked spectacular. It was backlit by the rising sun, and intermittent lightning flashed against its dark gray clouds.

Theoretically, I was headed to Mt. Wilson. It was July. It was hot. It was time to get on the ANFTR/Mt. Disappointment race course! But was that going to be a good idea? A slight chance of a thunderstorm was forecast for the afternoon and already there was an active storm right in front of me.

The Angeles National Forest Trail Races (aka Mt. Disappointment) is a popular event usually run in the heat of Summer after the Fourth of July. Because of the pandemic, Bobcat Fire, and trail and road closures, the race has been on hiatus since 2020, but a new race date appears to be in the works!

Another ragged bolt flashed horizontally across the clouds. The cell looked isolated and appeared to be moving to the north. I decided to take a chance and bet that the morning storm was a quirk. Still, it suggested a real possibility of a thunderstorm later in the day.

About the time I passed Trail Canyon on Big Tujunga Canyon Road, it started to rain, and the rain continued much of the way to Red Box. The activity was actually more extensive than the cell near Mt. Lukens — a band of thunderstorms had swept through the San Gabriel Mountains between Mt. Lukens and Mt. Wilson.

Mt. Wilson Road was still wet as I started down the first leg of the ANFTR/Mt. Disappointment 60K/50K/25K courses. If you have to run on pavement, running downhill on super-scenic Mt. Wilson Road after a thunderstorm is about as good as it gets! The cleansed atmosphere and vivid smells in the wake of the storm were remarkable — as were the views down into the canyon of the West Fork San Gabriel River.

This morning, I was doing the 25K course, but all the distances follow the same route to Red Box. They start by running down Mt. Wilson Road to Eaton Saddle and then following Mt. Lowe Fire Road through Mueller Tunnel to Markham Saddle and the San Gabriel Peak Trail. The San Gabriel Peak Trail leads up to the Mt. Disappointment service road and, surprisingly, the high point of the 60K/50K/25K courses. This stretch of service road is higher than the start/finish on Mt. Wilson!

Even if you have run a trail many, many times — and think you’re familiar with it — sooner or later, you’re going to encounter something you didn’t expect. From the Mt. Disappointment service road, the ANFTR/Mt. Disappointment courses turn onto the Mt. Disappointment/Bill Riley Trail. After the first couple of switchbacks, there were an increasing number of cut limbs on the trail. Initially, the cuttings were not much of an issue, but became worse as I continued down the trail.

Partway down, I encountered two very upset hikers who had lost the trail. They had just decided to leave the trail and hike on the service road. They cautioned me that the section where they had problems was just below. They weren’t kidding. I’ve done this trail innumerable times and at one point also had difficulty locating it. I had to wade through an expanse of cuttings to stay on the trail.

I’ve been on trails impacted by forest thinning projects before. The crews that worked on those projects at least made an effort to keep the trails clear. No such attempt was made here — the cuttings were left where they fell, and if that was on the trail, too bad!

It was a relief to get off the Mt. Disappointment/Bill Riley Trail and down to Mt. Wilson Road and Red Box.

Update October 2, 2024. I ran the ANFTR 25K Course on Sunday and the cuttings on the Mt. Disappointment/Bill Riley Trail had been removed. The trail was clear and back to normal!

Unlike last year, Rincon-Red Box Road was in great shape. It was so well-graded that a Prius might have been able to drive down to West Fork. Much of the 5.5 miles down to West Fork are in full sun, so the temperature has a substantial impact. In the 2019 ANFTR/Mt. Disappointment 50K, the thermometer on my pack read about 80 degrees. In the 2017 50K, the temp on the same stretch was about 100 degrees. Today, it was around 90.

Whatever the temperature, there are excellent views down the West Fork and of the Mt. Wilson area. The towers on Mt. Wilson always look tantalizingly close, and the climb up Strayns Canyon doesn’t look that bad. (Ha!) Like last year, there were four or five creek-like crossings of the West Fork San Gabriel River.

The area around the spring at West Fork was a bit overgrown, but a trampled path through the grass below the cistern led to the outflow pipe. I refilled my hydration pack and drank my fill before setting off on the Gabrielino Trail. With the temperature in the sun at West Fork around 95, I should have spent more time at the spring cooling down.

It’s only about 1.6 miles from the spring to where the Kenyon Devore Trail forks left off the Gabrielino Trail, but it often seems longer. Probably because I’m anticipating the turnoff and don’t want to miss it. This morning, it was also the hottest stretch on the course, with the temperature in the sun topping out at around 100 degrees.

Based on some recent runs, I expected the Poodle-dog bush on this stretch to be a problem, but most of the Poodle-dog bush had been trimmed or was wilting. It wasn’t the only thing that was wilting. Shortly after turning off the Gabrielino Trail and onto the Kenyon Devore Trail, the combination of heat and humidity hit me like the proverbial brick. I had to back off the pace.

Not long after that, I was startled by a runner coming up behind me. It turned out to be another runner from the West San Fernando Valley! Charlie was training for UTMB and putting in a tough 27-mile, 8700′ gain day. We had a great conversation about races, running, and adventures in the mountains. Despite the heat, he was moving well and soon disappeared up the trail.

I continued chugging up the trail, noting familiar features as I climbed higher and higher. Eventually, the white dome of the Hooker 100 inch Telescope came into view, and I knew I just about done!

As I worked up the final half-mile of trail, I could see only a couple of isolated build-ups of cumulus clouds. One was over the desert and the other was to the east near San Gorgonio. The sky over Mt. Wilson was mostly clear.

Here’s a high-resolution, interactive, 3D-terrain view of the Mt. Wilson – Red Box – West Fork – Kenyon Devore Loop. The loop is a slightly shorter version of the ANFTR/Mt. Disappointment 25K.

Some related posts:

– After the Bobcat Fire: Running the ANFTR 25K Course

– An ANFTR/Mt. Disappointment 2020 Adventure