Update 09/25/08. According to Columbia Sportswear customer service, the Continental Divide style is in the Fall ’08 line, but will not be continued in Spring ’09.

Update 09/18/08. Sadly, according to Columbia Sportswear customer service, the Vitesse style is no longer being produced and their current inventory of the Vitesse for the fall ’08 season is limited.

Update 01/23/08. My latest pair of Vitesse’s (made in China) seem to be a very different shoe than the dozens of pairs in which I’ve run before. They seemed to be short for the size, a little more narrow in the forefoot, and the cushioning and shock absorption didn’t feel up to par. Montrail was purchased by Columbia Sportswear about a year and a half ago and according to a customer service rep, “manufacturing of the shoes moved to new factories.” An ultrarunning friend had a similar sizing problem with his last order of two pairs of Vitesses, but said the cushioning was OK. Maybe my latest pair was an aberration. I hope so.

Update 08/19/07. Each of my last two pairs of Continental Divides have weighed more than the first pair. The second weighed 30.6 oz./pair, and the third weighed 32.0 oz./pair! My last two pairs of Vitesses have weighed in at 27.0 oz./pair. At only 24.2 oz./pair, the adidas Trail Response 14 is my most lightweight trail running shoe.

Many runners are fanatical about their shoes. Trail runners are no different, and every runner has their favorite. For several years my favorite trail running shoe has been the Montrail Vitesse. This is a shoe that straight out of the box, I would not hesitate to wear in a tough 50K. I’ve had a couple dozen pairs, and usually have 3-4 pairs that I rotate through from run to run.

It’s not that I haven’t tried other shoes. In their rush to jump into the rapidly expanding trail running shoe market, many well known and respected manufacturers of outdoor gear proffered up at least one trail running entry, and I tried a bunch of them. Like so many over sized and accessorized SUVs, the look was the thing. Many of the shoes were just BAD. There’s no other way to say it.

The reality of the trail running shoe market is that the shoes aren’t just used for trail running. They are used in activities ranging from fitness walking to adventure racing. One early entry became a top seller – not because trail runners liked it – but because it became a trendy shoe on campus. Another bone jarring model left me shaking my head and wondering if the design had been tested by anyone that actually ran in it. Fortunately the trail running market continues to grow, and manufacturers are starting to better address the needs of those that run in the shoes.

So, what’s so special about the Vitesse? First and foremost is the fit. I’ve run 50 miles in the Vitesse and not bothered to take them off for the post race feed. Beyond the fit, it’s a shoe that runs well. It has good shock absorption and cushioning, and a smooth heel-to-toe transition. It’s not too stiff and seems to have a good balance of stability versus flexibility. The tread isn’t overly aggressive and performs well for me on most trail surfaces. Basically I can forget about the shoe and just run.

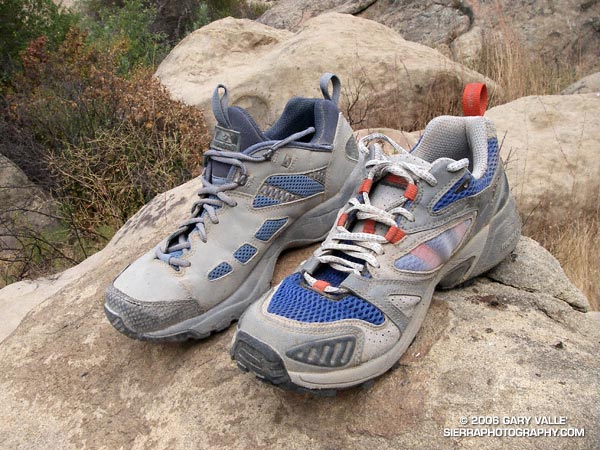

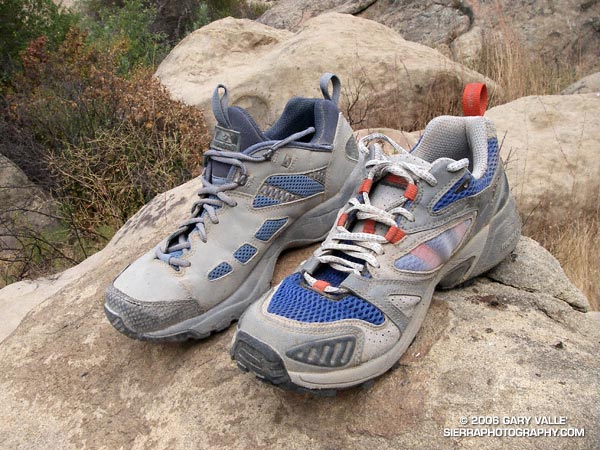

I’ve tried several of the newer Montrail designs, but none performed as well for me as the Vitesse. That is, until I tried the Continental Divide. I’ve had a pair for about a month, and like the Vitesse, it’s a shoe that’s been comfortable from run #1. It is said to be a replacement for the Leona Divide, but it is a vastly different shoe. In my mind, it is closer in functionality and feel to the Vitesse.

There are some significant differences. The first thing I noticed (on a 100 degree day) is that the Divide is much better ventilated, and runs cooler than the Vitesse. It also seems to have better cushioning. The tongue and ankle cuff of the Divide are not integrated, as in the Vitesse, but the fit around the ankle is excellent and seems to keep out about as much debris.

If you pick up the shoe and twist it, you’ll see that the Divide is more resistant torsionally than the Vitesse. In combination with a medial post and heel strap, it seems to provide excellent stability, without feeling stiff, or obviously interfering in the natural action of the foot.

The outsole width and profile of the Divide is similar to the Vitesse, but lacks the lateral outrigger. The tread pattern is reminiscent of the Leona Divide. Underfoot, it runs well, and seems to have somewhat better traction over a wider range of surfaces.

There are always design trade-offs, and the Continental Divide is no exception. Because they are better ventilated, a little more fine dirt finds its way into the shoe on dry, dusty trails. Your socks will also get wet more quickly in damp conditions – say running through wet grass – but will also dry out more quickly. Another consideration is that the Divide is slightly heavier than the Vitesse (1.4 oz/pair on my scale), and costs about $20-$25 more.

Update 08/19/07. Each of my last two pairs of Continental Divides have weighed more than the first pair. The second weighed 30.6 oz./pair, and the third weighed 32.0 oz./pair! My last two pairs of Vitesses have weighed in at 27.0 oz./pair. At only 24.2 oz./pair, the adidas Response Trail 14 is my most lightweight trail running shoe.

I happened to be wearing the Continental Divide when I got caught in a violent thunderstorm on a 20 mile run at Mt. Pinos, California. The trail conditions were as challenging as they get – torrential rain and hail on steep, storm-gnawed, rock strewn trails. The Continental Divide never skipped a beat.