Sprawling oaks along the Blue Canyon Trail.

From this morning’s run of a variation of the XTERRA Boney Mountain Trail Run course.

Sprawling oaks along the Blue Canyon Trail.

From this morning’s run of a variation of the XTERRA Boney Mountain Trail Run course.

The temperature was in the low fifties, but with a 20 mph wind it was cold. I had just run up the Chumash trail, and was on my way down. The sun was nearing the horizon and hidden by a band of clouds. It had been like that since I topped out at Rocky Peak road. I hoped by the time I reached a vantage point of Chumash Rocks the setting sun would break underneath the clouds and illuminate the formation.

Nope. When I reached the viewpoint, the rocks were still in shadow. And the wind was even stronger. Squeezed between two hills, it rushed through the little col in cold, turbulent gusts. Buffeted by the wind, and chilled to the bone, I waited for the sun.

And waited. It was too cold to just stand there. I took a few photos, but the sun and clouds were not cooperating. At some point, minutes away, the sun would set, and that would be that. The photo just wasn’t going to happen. I returned to the trail and began to run down the hill.

In the lee of the hills the wind lessened, and it was not so cold. It was still a few minutes before sunset, and as I rounded a corner I could see a bright glow at the edge of the clouds.

I was several hundred yards down the trail when the first hint of sunlight appeared on a distant hill. It was veiled and muted, but it was sun. Maybe there was time. I turned and hurried back up the trail.

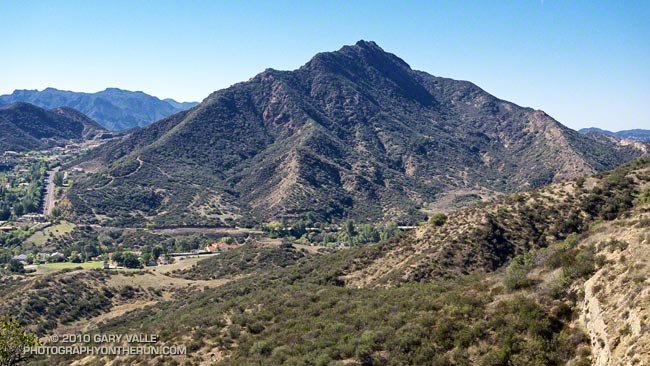

I wasn’t familiar with the routes on Ladyface, and wasn’t certain I could get to the peak directly from the Heartbreak Ridge trail. But that’s part of the fun of an adventure run. I had a general idea of what I wanted to do — an out and back from the Phantom trailhead in Malibu Creek State Park to the top of Ladyface. And I had an idea of the time available to do it — about four hours. The details would sort themselves out along the way.

Or at least that was the theory. It was now three in the afternoon, and I was one hour and 56 minutes into sorting out those details. Theoretically, I was supposed to be on the summit of Ladyface in about four minutes.

Earlier, I had run out of trail descending Heartbreak Ridge, and had used a network of coyote paths to get down to Cornell & Kanan roads. But then I chosen the wrong “trail” to start the climb of the peak.

For sure the route would follow one of the prominent ridges on the east side of the mountain. Since the descent of Heartbreak Ridge left me on the northeast side of the peak I had looked for a route there. One car was parked at the start of a dirt road, and a street vendor had indicated he’d seen people start the climb there. My thought was that maybe an established trail would work up the canyon and onto the northeast ridge.

Wrong Charlie Brown! The trail, which (ha!) turned out to be a freeride course, was a dead end. Following it burned about 10 minutes and a good chunk of elevation gain. I ran down and jumped up onto the northeast ridge, where I found a use trail.

Low on the ridge it looked like this trail might go to a subsidiary peak and not the true summit of Ladyface. Whatever it did, I was now short on time, and committed to this approach. I would follow it until either I ran out of time, or reached a summit.

The face was deep in shadow and wet from Friday night’s rain. Still a couple hundred vertical feet below its top, I zig-zagged up through the steep outcrops of Conejo volcanic rock. It wasn’t how I had pictured the trail on Ladyface, and I hadn’t expected to be climbing on wet, mossy holds for the second weekend in a row.

Two hours and 3 minutes into the adventure I scrambled onto the summit. A surprised hiker asked, “Where did you come from?” I explained, and he commented, “I’ve never climbed Ladyface that way.”

I jogged down the well-used, but somewhat manky trail on the east/southeast ridge, followed Kanan back to Cornell Rd., climbed back up Heartbreak Ridge, and made it back to the car a couple of minutes after five o’clock.

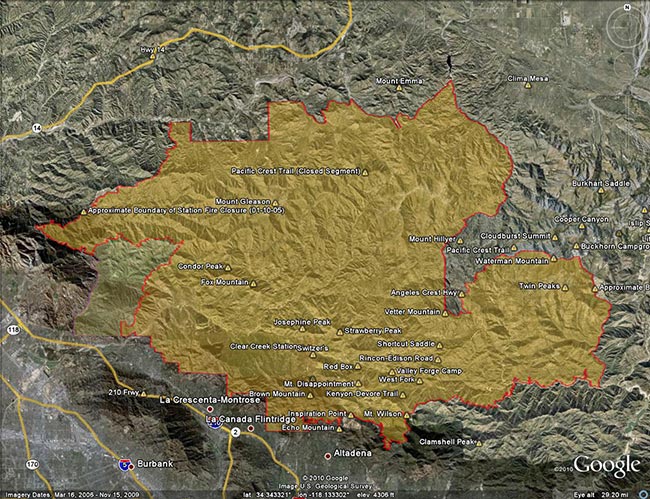

Update Friday, May 13, 2011. Good news! Effective Monday, May 16, 2011, Angeles National Forest is reopening about half of the area of the Forest currently closed as a result of the Station Fire. This reduces the closure area from 186,318 acres to 88,411 acres, and opens most of the burn area south and east of Angeles Crest Highway (Hwy 2) from Bear Canyon east to Twin Peaks. Some of the trails and areas opened are the Sunset Ridge Trail, Bear Canyon Trail, segments of the Gabrielino Trail, Nature’s Canteen Trail, San Gabriel Peak and Mt. Disappointment, Valley Forge Trail, Kenyon DeVore Trail, Silver Moccasin Trail, Pacific Crest Trail (some rerouting), Twin Peaks and the Mt. Waterman-Twin Peaks Trail from Three Points. For more information see the news release, detailed map, and other information related to Closure Order No. 01-11-03 on the Angeles National Forest web site.

On September 20th, after issuing a press release with the title, “Angeles National Forest reopens areas offering hiking, picnicking,” Angeles National Forest (ANF) reopened about 5 percent of the Station Fire closure area, and extended the closure of the remaining 186,320 acres another year to September 19, 2011. Here’s an ANF map of the revised closure area (PDF).

According to the press release, most of the areas burned in the Station Fire remain closed “for public safety.” When will these areas reopen? In the press release former ANF forest supervisor Jody Noiron states, “The Forest Service intent is to reopen areas severely damaged in the fire over the next few years as conditions allow.”

It’s hard to understand the rationale for the extent and duration of this closure. Over the past year, many dedicated forest users have participated in permitted work parties and events in the closure area. We’ve been on the trails and roads. We know firsthand that many miles of trails and dirt roads are passable, and much of the closure area could reasonably be in use.

Remarkably, a year after the fire, the size of the Station Fire closure area remains LARGER than the area burned by the fire! Some areas in the Forest that were burned are open, and some large areas that did not burn are closed.

Other than the boilerplate “to protect natural resources and provide for public safety” in the closure order, and some bureaucratic arm-waving, there has been very little information released documenting why these areas of ANF should remain closed.

According to an article posted on the Pasadena Star News web site (08/22/10 by Beige Luciano-Adams), acting ANF forest supervisor Marty Dumpis said, “It’s not just safety but also we have to allow the area to recover because if we allow people to start trampling over regrowth then they’ve just set it back another year. We hope people will be patient enough, allow natural recovery to begin, and then we can get some of these areas open.”

Is that the way Angeles National Forest higher-ups see us? The hikers, runners, and riders that most frequently use these trails are among the most experienced that visit the Forest. Trails constrain use, and are a minuscule part of the recovery area. If credible evidence exists that trail use would delay the area’s fire recovery, Angeles National Forest should make it available to the public.

To keep such a large area of public land closed for such an extended period following a Southern California fire is unprecedented. Even in the case of the largest Southern California fires, the Cedar and Zaca fires, closed areas in Cleveland and Los Padres National Forests were reopened within a year of the fire. In many cases fire closures in the National Forests of California have been lifted within days or weeks of a large fire. This reflects a general policy that closures be implemented and maintained as a last resort.

In a 2009 presentation following the Station Fire, Jody Noiren noted that Angeles National Forest:

– provides 72% of all open space in Los Angeles County

– has 17 million people living and working within 1 hour drive

– has 3.5 million visitors per year, of which half come from within a 50 mile radius of the Forest

It may simplify forest management, and be more convenient for the Forest Service to keep such a large area of Angeles National Forest closed, but it is clearly not in the public interest. Extending the Station Fire closure will not enhance recovery, increase protection of sensitive species, or prevent the spread of invasive plants. But it will deprive millions of people living and working nearby of an indispensable and intrinsic public resource.

Long experience in Southern California demonstrates that public lands can be reopened in a timely fashion following a fire without abusing resources, or putting the public in undue peril. It is time to stop the doublespeak and reopen all but the most severely damaged areas of the Station Fire burn area to public use.

The Station Fire closure area is in the congressional districts of Rep. David Dreier [R-CA26] and Rep. Howard McKeon [R-CA25]. California’s senators are Sen. Barbara Boxer [D-CA] and Sen. Dianne Feinstein [D-CA]. Determine and contact your Representative and Senators.

Did a variation of the “Phantom” loop in Malibu Creek State Park this morning. The basic loop links together the Grassland, Liberty Canyon, Phantom, Cistern, Lookout, Yearling, Deer Leg, and Cage Creek Trails, as well as Crags Rd.

The peak in the haze on the left of the photograph in the distance is Saddle Peak. The peak on the right is Brent’s Mountain.

Originally posted 5/27/07. Previously updated 9/15/10. Scoping letter info added 12/22/13. Draft EIS info added 8/21/18.

Update 8/21/18. Nearly 13 years after the closure of Williamson Rock and a key segment of the Pacific Crest Trail, the Forest Service has released a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Williamson Rock Project. The public comment period is from July 27 to September 10, 2018. For additional information see the Forest Service Williamson Rock Project page and the Access Fund page REOPEN WILLIAMSON ROCK TO CLIMBING!

Update 12/22/13. New Williamson Rock/PCT scoping letter, dated 12/18/13, from Angeles National Forest to “consider resuming recreation opportunities in the currently closed area, in and around Williamson Rock.”

————

Located in Angeles National Forest (ANF), Williamson Rock is an area of exceptional scenic and recreational value. Because of its proximity to Los Angeles, variety of climbing routes, scenic beauty, and moderate summertime temperatures, it is one of the most popular rock climbing areas in Southern California.

In December 2005, in order to protect critical habitat of the mountain yellow-legged frog (MYLF), the Forest Service “temporarily” closed approximately 1,000 acres in the upper Little Rock Creek drainage in the San Gabriel Mountains. The closed area includes Williamson Rock, and the Pacific Crest Trail between Eagle’s Roost and the Burkhart Trail.

In May 2007 the Forest Service issued a press release and scoping letter proposing an access trail and initiating an environmental analysis. Now, nearly five years after the “temporary” closure of Williamson Rock, and following many delays, Angeles National Forest has completed a draft Environmental Assessment (EA) whose bottom line recommendation is to extend the closure another three years!

In the draft EA, the Forest Service says the extension is needed,”while neighboring [MYLF] population segments are given time to rebound from the effects of wildfire and consequent watershed emergency.”

The Forest Service’s recommendation to extend the closure is based on a false premise, that closure of MYLF habitat, and adjacent land, will protect the MYLF population. There is substantial evidence that this is not the case. This was recognized in the 1999 paper (Mahony, et al.) in which researchers assessed the disappearances and declines among Australian frogs and proposed methods to prevent further losses:

“It is generally accepted that the least expensive way of preventing extinction and loss of biodiversity is the maintenance of habitats. This argument is well established in the conservation biology literature (Caughley and Gunn 1996), however, it does not consider or deal with a situation such as that which currently faces frogs in Australia and globally. One of the puzzling features is that species have disappeared from areas of pristine or near pristine habitat and areas of large reserves where there are no indications of habitat destruction. Similarly, there is no evidence that an introduced competitor or predator is responsible, apart from the hypothesis that an introduced pathogen is involved (Laurance et al. 1996). Preservation of habitat or declarations of new reserves would not have halted or prevented the loss of the majority of species.”

Since this paper was published, there has been much research in this area, and there is a growing body of evidence that global declines in many species of frogs, including the MYLF, is due to infection from the chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd).

It is believed that the fungus is spread through its own movement in water, the flow of water, and by the activity of infected amphibians. Because infection has occurred in pristine, widely separated populations, it is hypothesized that other vectors, such as birds, fish, animals or insects, could play an important role in its spread. Research has shown that spread by birds and other mechanisms are a possibility (Johnson & Speare, 2005). It is also a possibility that Bd has been present in amphibian populations worldwide for some time (Rachowicz et al., 2006).

In support of its recommendation that the Williamson closure should be extended, the EA states, “Indirect impacts to the frogs include the spread of pathogens, such as chytrid fungus, inadvertently carried into the habitat by visitors.”

I have found no published evidence that recreational activities, such as rock climbing, are the proximate cause of the spread of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis into MYLF habitat. It would seem especially unlikely in the context of rock climbing in usually warm and dry Southern California. Desiccation kills the fungus. In the 2005 study by Johnson & Speare, in which zoospores and zoosporangia were introduced on feathers, under most circumstances the fungus became inviable after 2 hours of drying.

According to the EA, all remaining units of the Southern California distinct vertebrate population segment (DPS) of the MYLF have already been confirmed positive for presence of Bd. This suggests that a frog unaffected by Bd is much more likely to be infected by natural mechanisms and vectors from within the infected population rather than by Bd brought into the habitat by a human visitor.

Under the EA’s Alternative 3 (The Recreational Development Alternative), in which climbers would be routed away from MYLF habitat, the probability of climbers spreading Bd from outside the habitat, or physically harming the frogs, or disrupting their habitat, would appear to be almost nil.

Rather than extending an unnecessarily prohibitive closure that is unlikely to benefit the MYLF, a plan such as Alternative 3 (The Recreational Development Alternative) should be adopted, and Williamson Rock reopened to climbing.

—

The efforts of the climbing community are being coordinated by the Friends of Williamson Rock in partnership with the Access Fund and the Allied Climbers of San Diego. The Access Fund is a national, non-profit climbers’ organization dedicated to preserving the natural resources used by climbers, and climbers’ access to those resources.

Comments regarding the draft EA, and the recommendation to extend the closure of Williamson Rock for another three years, must be submitted by October 1, 2010. Send to:

Darrell Vance

Attn: Williamson Rock Environmental Assessment

701 N. Santa Anita Ave.

Arcadia, CA 91006

Email: dvance@fs.fed.us

For more information, see the Access Fund Williamson Rock page.

The photograph of Williamson Rock was taken on the PCT while doing the run Pleasant View Ridge on July 2, 2006.

Related post: Complications