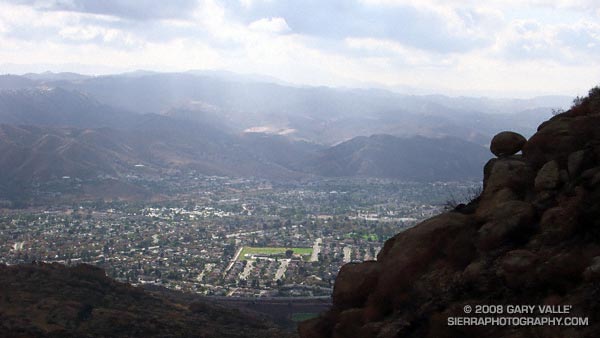

A view of the eastern Simi Valley and Simi Hills from Rocky Peak.

From a run in Rocky Peak Park today.

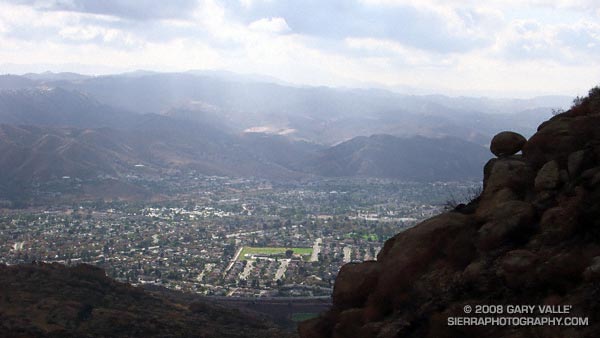

A view of the eastern Simi Valley and Simi Hills from Rocky Peak.

From a run in Rocky Peak Park today.

When I woke to the rumble of thunder, rain pounding the roof, and wind roaring in the trees, I wondered if a planned run of the Boney Mountain Half Marathon course with John Dale was going to turn into an epic. Radar and satellite imagery showed subtropical moisture streaming in from the southwest, producing bands of showers and thunderstorms. Things don’t always look as bad at the trailhead as they do on weather radar, so I grabbed my gear and headed for Wendy Drive.

The weather looked promising driving through Agoura, but the further west I drove, the more ominous the skies became. Somewhere around Lynn Road KNX announced that the NWS had issued a severe thunderstorm warning for the Santa Clarita area, with cloud to ground lightning, heavy rain, possible damaging winds and dime-sized hail. It was with that thought in mind, and a shower pelting the car, that I pulled into the parking area on Potrero Rd.

If anything, weather is fickle, and sometimes that quirkiness can work for you. There was an area of heavy rain to the west, but the activity appeared to be skirting the area, so we opted to start the run.

There were a few sprinkles as we jogged down the blacktop into Big Sycamore Canyon, and a few more as we did the first easy mile of the Hidden Pond Trail. Down in the canyon it was hard to tell what the weather was doing, but after gaining some elevation we reached a better vantage point. Just a few miles away thunderstorms were being swept northeast from the Santa Barbara Channel, across the Oxnard Plain, and into the Ventura Mountains.

Skies darkened and the shower intensity increased as we ran down Ranch Center Fire Road. The wind was blowing in the fitful gusts that precede a thunderstorm, and it felt as if the sky might fall at any moment. With a slight shift in the track of the thunderstorms we might be running in a deluge, dodging lightning strikes.

But it didn’t shift. Following the shower, the sun broke through the clouds just long enough to add glints to the raindrops dripping from the leaves of sycamores and oaks in Blue Canyon. Under overcast skies, we climbed up the Old Boney Trail and into the Boney Mountain Wilderness.

We had not seen a hiker, runner, or rider since turning onto the Hidden Pond Trail early in the run. So it was a bit of a surprise when we rounded a corner and ran into Ed Reid and several other volunteers with the Santa Monica Mountains Trails Council doing trail maintenance on a section of the Old Boney Trail.

Just about any weekend of the year, dedicated members of the SMMTC will be somewhere in the Santa Monica Mountains, working on a trail. To get a better idea of the amount of work done and the number of trails involved, take a look at this list of recently maintained trails! How many of these have you hiked, run or ridden?

There are several ways to help support SMMTC:

See the Santa Monica Mountains Trails Council web site for more info.

Some related posts: Boney Mountain Half Marathon, Return to Hidden Pond

The scat appeared to be a day or two old, and was much bigger than a coyote’s. It was full of fur and could only be from one animal — a mountain lion. The spot had been used before, and it probably wasn’t a coincidence that this was one of the few points along the trail with a good view and nearby cover. I looked into the brush and wondered if unseen eyes looked back.

The sun was well above the horizon, but the first gusts of a developing Santa Ana wind kept the morning cool. No one was on the trail ahead or behind me, and the best I could tell, I was the only two-legged creature within sight.

Walking slowly from the spot, I surveyed the secluded valley. Perched on the edge of the coastal mountains, La Jolla Valley is extraordinary. Surrounded by wind-sculpted peaks, it is situated above and to the west of Big Sycamore Canyon. Its bottom is carpeted with areas of native and non-native grass. Only a tiny percentage of California’s native perennial grasslands remain, and like the big trees, they are relics of the past. Preservation of this native grassland is probably due to the valley’s proximity to the ocean, and its unique microclimate.

Here, trails have been run and peaks climbed for thousands of years. (Charcoal at an archaeological site in the valley has been dated to a maximum age of 7000 B.P.) Above me a raven calls, and Spirit-like, a gust of wind rustles through the grass. Respectfully, I continue running in the direction of Mugu Peak.

—

The run from Wendy Dr. was more moderate than expected. The first 3 miles of Sycamore Canyon Fire Road are paved, and whether on the fire road, or the single track trails that parallel the road at times, a fast pace can be maintained down to the junction with Wood Canyon Fire Road.

The Wood Canyon Vista Trail/Backbone Trail takes off right (west) from Sycamore Canyon Fire Road a short distance past the Wood Canyon Fire Road junction. It is moderately graded and very runnable. At it’s top a short zig right (north) on the Overlook Fire Road leads to the La Jolla Valley Fire Road, which can be followed left (west) down into La Jolla Valley.

Many, many variations of this course are possible. Here are archived maps of Rancho Sierra Vista/Satwiwa and Pt. Mugu State Park originally from the NPS Santa Monica Mountains web site. Also see the Pt. Mugu State Park maps on VenturaCountyTrails.org.

Depending on whether you want the beta, a little time in Google Earth should help clarify the options. This particular course worked out to about 21 miles, with about 2200 ft. of elevation gain/loss. Here’s a Google Earth image and 3D interactive view of a GPS trace of my route.

It’s fun to link together several trails into a loop, and it’s even more fun when the trails are single-track, or at least have a single-track flavor. The Boney Mountain – Big Sycamore Canyon circuit links together segments of more than ten trails and roads in Rancho Sierra Vista/Satwiwa and Pt. Mugu State Park. The route is characterized by airy ridges, steep climbs, wide-ranging views, towering rock formations, and one of the best downhill running segments in the Santa Monica Mountains. Today’s run expanded the loop, adding even more single-track trail — and elevation gain.

This route also climbs over Boney Mountain and descends the Chamberlain Trail segment of the Backbone Trail. However, at the Old Boney Trail junction, instead of descending to the Danielson multi-use area on the Old Boney Trail (northbound) and Blue Canyon Trail, this route follows the Old Boney Trail (westbound) to Sycamore Canyon Fire Road.

From the junction of the Old Boney Trail with the Sycamore Canyon Fire Road the goal is to hook up with the Coyote Trail, which can be seen switchbacking steeply up a slope on the other side of the canyon. We did this by continuing about 0.5 mile down Sycamore Canyon Fire Road, and then turning right on Wood Canyon Fire Road. The Two Foxes Trail starts a short distance up the fire road, and in about 0.4 mile leads to the start of the Coyote Trail. Once on the Coyote Trail it is about 2.3 tough — and often hot — miles to the start of the Hidden Pond Trail at Ranch Center Road. The rest of the route is the same as in the Boney Mountain – Big Sycamore Canyon circuit.

All in all the course is about 21 miles long, with 4000 ft. of elevation gain/loss. Here’s a Google Earth image and Google Earth KMZ file of a GPS trace of the route.

Most of the trail between Mt. Pinos and Mt. Abel is in old growth pine and fir. One exception is this area of downed trees near the Cerro Noroeste road. The brushy plant with yellow flowers is rabbitbrush (probably Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus).

From today’s run to Mt. Abel and back from Mt. Pinos on the Vincent Tumamait Trail in Los Padres National Forest.

Following are brief descriptions, Google Earth images, and a Google Earth KMZ file of several trail runs at Ahmanson Ranch — now Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve. These are shorter courses, generally on dirt roads, that extend as far west as Las Virgenes Canyon. Some longer runs in this area are listed in the Santa Monica Mountain Conservancy Open Space section of my Google Earth KMZ Files of Trail Runs page.

The distances and elevation gains/losses specified are for a round-trip from the Victory trailhead, and are approximate. Any of the courses can be lengthened by 2.6 miles by starting at the El Escorpion Park trailhead at the west end of Vanowen. This also adds about 350′ of elevation gain/loss.

To simplify labeling the courses, the main (dirt) road between the Victory trailhead and Las Virgenes Canyon is referred to as the “Main Drag.” This term was coined by long-time Ahmanson runner Jon Sutherland. The Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve map refers to this road as the East Las Virgenes Canyon Trail. The road also has been designated a segment of the Juan Bautista De Anza National Historic Trail.

Here is the Google Earth KMZ file for the trail runs described below. To avoid clutter, when the file is opened in Google Earth, only two of the courses are initially displayed. Additional runs and variations can be viewed by clicking on the checkbox for the course.

If you are new to running at Ahmanson, a couple of things to watch out for are rattlesnakes and the heat. It also gets very muddy when it rains. Enough talking, let’s get to running…

Lasky Mesa Mary Wiesbrock Loop (3.7 mi, 270′ gain/loss)

Of the courses listed, this run has the least amount of elevation gain. Following a short stretch of downhill, the route does a big switchback and climbs up to the eastern shoulder of Lasky Mesa. The climb is fairly moderate, but comes early in the run. About 1.2 miles from the Victory parking lot is a “Y” junction, marked by some rocks and a trashcan. (A pair of ravens also like to hang out here.) This is the start of the 1.3 mile loop that honors Mary Wiesbrock, whose tireless efforts helped save Ahmanson Ranch from development.

If you do the loop counterclockwise, taking the right fork at the “Y,” in about 0.6 mile the Mary Wiesbrock loop turns left (south) onto a connector road. This leads to a “T” junction and the southern leg of the loop. A left turn at the “T” continues east through grassland to some ranch buildings, and another left leads back to the “Y” at the start of the loop. All of the loop is on dirt road, and there are some trail markers.

If you miss the turn onto the north-south connector, the north road continues to an overlook at a prominent Valley Oak on the western end of Lasky Mesa. From this point the extension of the south road can be used to return to the standard route and the “Y” junction. This extended version of the Mary Wiesbrock loop increases the length of the course to 4.25 miles.

Main Drag – Lasky Mesa Loop (3.7 mi 380′ gain/loss)

Except for a short stretch at its beginning and end this course is a complete loop. It starts the same as the Lasky Mesa Mary Wiesbrock Loop, but instead of turning left up the big switchback, it turns right onto the Main Drag. Here, the road curves downhill and then turns west. After passing through a grassy riparian area, the road climbs a short hill and continues westward.

About a mile from the parking lot, a prominent oak tree can be seen on the crest of hill, directly south of the road. This is the “lollipop tree.” In about a tenth of a mile, at a junction with a trashcan and trail marker, this course forks left (south) off the Main Drag , and drops down to another grassy riparian area along the main drainage of East Las Virgenes Canyon. From here the road climbs about 1/2 mile up to Lasky Mesa.

At the top of the climb the road intersects the northern leg of the Mary Wiesbrock Loop. There are three route choices here. This course curves left (east), and then forks left and follows the winding road along the scenic northern edge of Lasky Mesa through valley oaks to the “Y” junction of the Mary Wiesbrock Loop. From here it’s a little over a mile back to the parking lot.

A slightly longer variation also curves left at the top of the hill, but forks right and continues south up a short grade. This leads to a “T” junction and the southern leg of the Mary Wiesbrock Loop. Continuing on the loop counterclockwise, this variation circuits Lasky Mesa’s grasslands around to the same “Y” junction as the standard course.

The third, and longest, variation turns right at the top of the long climb, and does the extended version of the Mary Wiesbrock Loop counterclockwise around the mesa to the “Y” junction.

There is also a scenic 3.3 mile variation that branches from the standard route in the grassy area just before the long climb, and ascends a well-used single track southeast to Lasky Mesa just west of the “Y” junction of the Mary Wiesbrock Loop. A left turn (east) here leads to the “Y” junction in about 200 yards.

Out & Back to Las Virgenes Canyon (5.3 mi, 465′ gain/loss)

This course starts the same as the Main Drag – Lasky Mesa Loop, but instead of turning left a little past the Lollipop tree, it continues west on the Main Drag all the way to Las Virgenes Canyon.

This is a good course for a tempo run — particularly the out leg to Las Virgenes Canyon. When the weather is hot the return leg (gradual uphill, often with the wind) can be tough.

If this run is extended to the Las Virgenes Rd. Trailhead it adds about 0.8 mile to the out and back course.

Las Virgenes Keyhole Loop (6.6 mi, 625′ gain/loss)

This is an excellent and varied course that loops through Las Virgenes Canyon and crosses Las Virgenes Creek twice. Following Winter rains you might even get your shoes wet!

The run starts the same as the Out & Back to Las Virgenes Canyon, but turns right (north) off the Main Drag at a junction (with a trashcan) at about the two mile point. From here, it is about a mile to Las Virgenes Canyon, and another mile down the canyon to the turn back onto the Main Drag.

There is a 7.3 mile variation of this course that turns south off the Main Drag about 1/3 mile east of Las Virgenes Canyon and follows a pipeline service road up to the western end of Lasky Mesa. This climb is known as “The Beast.” Some other roads/trails in this immediate area are posted “Restoration Area — Please Keep Out” so be sure you’re on the right trail.