Overcast skies and muted Fall color in Bear Canyon in the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California.

From the Red Box – Bear Canyon Loop Plus Brown Mountain run.

Overcast skies and muted Fall color in Bear Canyon in the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California.

From the Red Box – Bear Canyon Loop Plus Brown Mountain run.

Nearly every time I’ve climbed Mt. Baden-Powell I’ve wondered about the long ridge extending south from its summit. And nearly every time I’ve summited Baden-Powell I’ve been in the middle of another running adventure, and unable to explore more than a few hundred yards down the ridge. But today I wasn’t running to Eagles Roost or doing a long loop from Islip Saddle. Today the plan was to climb Ross Mountain, a peak far down on Mt. Baden Powell’s south ridge.

Major mountain ridges are often isolated, aesthetic and adventurous — characteristics that are magnets to mountaineers. While not technically difficult, the excursion to Ross Mountain is demanding. The first step is to climb Baden-Powell — a four mile trek with 2800′ of gain, that tops out at an elevation of about 9400′. From the top of Baden-Powell a use trail then leads down the south ridge three miles over varied terrain to Ross Mountain.

For the most part the use trail is relatively distinct and follows the anticipated route down the ridge. Even so, it is usually not as easy to follow a use trail as it is a conventional trail. It had rained a few days before, and the tracks of the last group to do Ross were vague. The most distinct tracks on the trail were from the recent passage of a bighorn sheep.

The route to Ross drops 2100′ in 2.5 miles, then ascends 200′ over the remaining half-mile to the peak. The descent is not continuous. About a mile from Baden-Powell the ridge is interrupted by a large bench, and there are other ups and downs along the way. The ridge can be seen in profile in this image or the PhotographyontheRun masthead.

The ridge projects into one of the more rugged areas of the San Gabriel Mountains — the Sheep Mountain Wilderness. To the west is the deep canyon of the East Fork, with Pine Mountain, Dawson Peak, Mt. Baldy and Iron Mountain towering above. To the west is the very remote canyon of the Iron Fork, sweeping up to form the 9000′ crest between Throop Peak and Mt. Burnham.

The ridge hosts a wide variety of conifers — limber pine, lodgepole pine, white fir, sugar pine, Jeffrey pine and even a few incense cedars. Life on the ridge is tough, and many of the trees are contorted, broken or stunted. It appears to have been a good year for the sugar pines, and some were heavily laden with cones. Overall the health of the trees on the ridge appeared to be good, with surprisingly few trees in obvious distress from the drought.

A little more than three hours after leaving Vincent Gap I zig-zagged up the final few steep steps to the 7402′ summit of Ross Mountain. Not unlike other vantage points along the ridge, the summit was a pretty spot under a sugar pine tree, but in this case with a small cairn and rain-soaked summit register.

After procrastinating a bit and checking out the south side of Ross Mountain’s elongated summit, I began the journey back to Baden-Powell.

Surprisingly, considering my plodding pace coming back up the ridge, it took almost exactly the same amount of time to get back to Vincent Gap as it had to go to Ross Mountain. As it worked out, the time lost on the climb back up the ridge was offset by the superb run down the Baden-Powell Trail.

According to my Garmin fenix 3’s barometric altimeter the total gain/loss on this adventure was about 5100′. If the gain/loss is calculated from the GPS track using 1/3 arc-sec DEMs it works out to about 5400′. The round trip distance was 14 miles.

Related post: Return to Ross Mountain

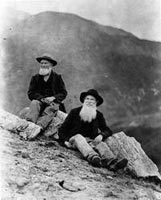

This photograph of Jason and Owen Brown (Los Angeles Public Library, Security Pacific National Bank Collection) is cataloged with the following description:

“Photo of Jason and Owen Brown, sons of John Brown of the Civil War and Abolition fame. View shows Jason and Owen Brown sitting on Mount Wilson, near the site of their cabin in 1884.”

Is the reference to Mt. Wilson accurate? Probably not. The peaks in the background establish they are not on top of Mt. Wilson. While they might be elsewhere on the mountain, it doesn’t seem likely. Mt. Wilson is more than five miles from their El Prieto cabin site. In his guidebook Trails of the Angeles, John Robinson describes the photo of the Browns as being “on Brown Mountain” — a peak which is near their El Prieto cabin, and which figured prominently in their lives.

Not having climbed Brown Mountain, I was curious to see if the photo of the “Brown Boys” was taken on or near its summit. Early this morning I set off from Red Box, Brown Boys photo in my pack, to do a loop through Bear Canyon and Arroyo Seco, and take a side trip to Brown Mountain along the way.

The detour to Brown Mountain began at Tom Sloan Saddle and followed the peak’s east ridge over several false summits to the summit of the peak. Brown Mountain’s rounded summit sits on the divide between Bear and Millard Canyons and on a clear day affords a panoramic view of the surrounding mountains and much of the Los Angeles area. Big views can lead to big dreams, and according to an article in the Los Angeles Herald in October 1896, the Boys had planned to build an observatory on the peak. While this was not built, the Boys did succeed in having the peak named in honor of their father

On the summit, and with the Brown Boy’s photo in hand, I faced first north over Bear Canyon, then east toward Mt. Disappointment, San Gabriel Peak and Mt. Markham; and finally south over Millard Canyon. Neither the terrain or skyline matched the photograph.

The best match I’d found today was on a peaklet near Tom Sloan Saddle looking southeast toward Inspiration Point. More likely the photo was taken on a ridge closer to their cabin. That adventure would have to wait for another day. Today the clock was ticking and I needed to retrace my steps back to Tom Sloan Saddle, descend Bear Canyon and then follow the Gabrieleno Trail up Arroyo Seco and back to Red Box.

Some related posts: Bear Canyon Loop Plus Strawberry Peak, Red Box – Bear Canyon Loop, Arroyo Seco Sedimentation

Following are a few photos taken along the way. Click a tile for a larger image and additional information.

Many of the hikers and runners that park at Vincent Gap climb Mt. Baden-Powell via the Pacific Crest Trail. The PCT isn’t the only trail that can accessed here and Mt. Baden-Powell isn’t the only hike. Vincent Gap is also the trailhead for the Manzanita Trail, Big Horn Mine Trail and Mine Gulch Trail. My run today involved these three trails.

First up this morning was the Manzanita Trail. The trail is part of the High Desert National Recreation Trail and connects Vincent Gap to South Fork Campground. It’s about 5.5 miles long and can be done as an out and back or as part of an approximately 23.5 mile loop that joins Islip Saddle, South Fork Campground, Vincent Gap and Mt. Baden-Powell.

That loop is a favorite and this morning’s short run on the Manzanita Trail was to check if a small stream/spring I use as a water source was still running. Remarkably it was!

Some work had been done on the trail since I was there in June. A washed out section just below Vincent Gap had been repaired, the tread in several places improved, and the indistinct trail across the rocky wash about a mile down from Vincent Gap had been much improved.

Some related posts: South Fork Adventure, Trail Running Weather, San Gabriel Mountains Running Adventure, Islip Saddle – Mt. Baden-Powell South Fork Loop

Each time I’ve run the segment of the Pacific Crest Trail between Inspiration Point and Vincent Gap I’ve been curious about a cluster of young pines in a burned area near Grassy Hollow. The trees appear to be older than similar areas of regrowth along the PCT between Mt. Baden-Powell and Little Jimmy Spring, which burned in the 2002 Curve Fire.

In turns out the area near Grassy Hollow was burned in the 18,186 acre Narrows Fire in 1997. That would make these trees about five years older than the Curve Fire regrowth.

Considering our huge precipitation deficit in Southern California over the past five years, the young trees in the Curve and Narrows fire areas seem to be doing surprisingly well.

Recently, I revisited the coast redwoods along Century Lake in Malibu Creek State Park . Several months ago I’d been disheartened to find many of these trees severely stressed by our five year drought. Several of the trees had lost most of their foliage. Based on my own photos and those from Google Earth, the trees had rapidly deteriorated in just a few months.

I started at the the westernmost redwood near the junction of the Forest Trail and Crags Road and worked east along the Forest Trail. I expected to see a decline in the trees since my last visit, but surprisingly that wasn’t the case. If anything the trees looked they might be doing a little better.

From west to east I counted about 16 trees or clonal clusters of trees. Of these, the trees on the bank of Century Lake appear to be the most severely impacted. At least one tree, with poison oak growing up its trunk, may have died.

A common drought response is for a plant to reduce its foliage. The size of its leaves may be reduced and leaf shape modified to reduce water loss. In some cases trees will become dormant and lose their foliage. Trees may also enter seasonal dormancy early and the period of dormancy may be extended.

It’s been my experience that trees respond to severe water stress in a manner similar to losing their foliage in a fire. One redwood that had appeared to be dead in March, now has new epicormic sprouts over the length of its trunk.

Another mechanism by which a redwood may survive the drought is by clonal sprouting from buds in its basal burl. It is common for coast redwoods to have numerous basal sprouts and sometimes these develop into additional trunks.

The easternmost redwood is of particular interest because it appears to be naturally-germinated. For now it is stressed, but surviving.

The survival of these trees is not only dependent on the drought, but climate factors such as temperature and fog frequency and persistence. Only time will tell if some of the trees are resilient enough to survive.

Related post: The Malibu Creek State Park Redwoods Are Dying