Note: This ascent of the Stone Canyon Trail was in the Fall, following five years of drought. On a Spring 2020 ascent, following a relatively wet period, there was a moderate amount of poison oak and some sections of the upper half of the trail were badly overgrown. In Spring 2021, a lot of work had been done on the trail and it was in excellent condition.

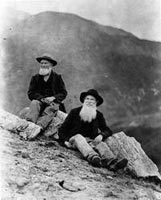

The last time I climbed Mt. Lukens was in the 70s. Drawn by its classic line, Phil Warrender and I climbed Lukens’ west ridge — a long, trailless ascent that started near the probation camp on Big Tujunga Canyon Road. Many years and many adventures later I was back on Lukens — this time on the Stone Canyon Trail.

Curious about the current condition of the trail, last night I read a few recent trip reports. It was a bit like reading tabloid news. If the reports were to be taken at face value, it would be a hellish, impossible to find, unmaintained, horribly overgrown, washed out trail that was lined with poison oak and poodle dog bush, and writhing with rattlesnakes.

It was evident in the first mile that the Stone Canyon Trail is a classic, no nonsense, ear-popping trail. First shown on the 1933 La Crescenta Quadrangle Advance Sheet, the route of the trail is pretty much the same now as it was then, starting near Wildwood in Big Tujunga Canyon and zig-zagging up the ridge just east of Stone Canyon to the summit of the peak.(The 1933 topo also shows a trail along the route Phil and I climbed.)

The Stone Canyon Trail tops out about a half-mile northwest of Mt. Lukins’ summit. Like many urban peaks, the summit is cluttered with electronics, but there are still worthwhile views on and near the top of the peak.

While on the summit, a LASD’s Air Rescue 5 helicopter flew by to the east — I guessed on the way to the Barley Flats staging area. But part way down the peak I heard the airship to the northeast and noticed a cloud of dust being stirred up from a turnout on Angeles Forest Highway. Once again Air Rescue 5 was at work. It’s astonishing how many calls they get.

Continuing to run down the trail I thought about some of the online comments I’d read the night before.

Hellish? Well, sure, on a hot day. Unless you’re looking to get in some heat training, don’t climb it on a hot day. Climb it when the weather is clear and cool!

Impossible to find the trail? Except for the big sign at the trailhead parking lot, I didn’t see any trail markers. But if you have a “big picture” view of where the trail is in relation to the parking lot, it’s not too hard to find.

Unmaintained? These days most trail maintenance is done by volunteers. A trail like the Stone Canyon Trail is kept alive through use, sporadic organized trailwork, and an occasional snip here and snip there.

Horribly overgrown? The higher you go the more overgrown it is, but today it was not yet to the point that serious bushwhacking was required. I wore running shorts. (But I almost always wear running shorts.)

Washed out? Yes, there were a few small washouts, and the margin of the trail has collapsed in a number of places. With care, all were passable. One of the washouts was a little larger, and required a bit more care than the others.

Poison oak and poodle dog bush? Maybe I missed it, but I didn’t see any poison oak. There was a minuscule amount of dried up PDB. (Ask me about the PO later in the week.)

Rattlesnakes? Always a possibility, even in Winter. But this is true in most areas of Southern California. In my experience the chance of encountering a rattlesnake is less from November through February, but there’s still a chance.

Ear-popping? The trail gains about 3,270 feet in 3.8 miles. My ears “popped” a couple of times on the way up.

Theoretically the gate on Doske Road is open from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. The Angeles National Forest web site showed the status of the Wildwood Picnic Site to be open, but the gate was not open today. I parked in the large turnout on Big Tujunga Canyon just west of the gate and ran about a half-mile on Doske and Stonyvale Roads to the parking lot and trailhead.