Seasonal snowfall in the mountains of Southern California is inconsistent at best. According to Tony Crocker’s Your Guide to Snowfall, in the past 20 years SoCal snowfall has ranged from a record high of 267 inches during the strong El Nino of 1997-98, to a low of 29 inches in 2013-14 during our prolonged drought.

So far this season, Your Guide to Snowfall’s total for SoCal is 143 inches, which is a bit above average and far more than we’ve had in recent years. After seeing the amount of snow on the higher peaks of the San Gabriels from Mt. Waterman a couple weeks ago, I was curious to see what the conditions were on the PCT between Islip Saddle (6650′) and Mt. Baden-Powell (9399′).

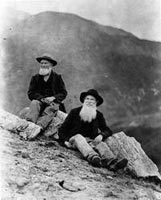

Joining me on today’s adventure was Patty Duffy. An avid outdoorsperson and ultrarunner, Patty did the JMT last year, and will soon be embarking on an epic border-to-border journey on the Pacific Crest Trail. Epitomizing the “hope is not a strategy” approach to challenges, today she was using much of the gear she would be using on the PCT — and in addition — carrying a sleeping bag, tent, stove and two days food!

Even though we started an hour later than normal, and temperatures had warmed the past couple of days, the snow on the shaded, north-facing slopes was still icy. Two hikers on their way down from Little Jimmy had trouble crossing one slippery slope. They had no crampons or micro-spikes and threw dirt on the snow to get by. It was obvious when we reached the area they described – a northeast facing gully. The slope was steep enough that a fall would have been very serious. Steep slopes, chutes and gullies are common along the trail between Islip Saddle and Baden-Powell.

The question of what is appropriate gear for hiking an icy trail in this kind of terrain doesn’t have a simple answer. Boots, “real” crampons, and an ice axe provide a lot of security when crossing a steep, icy slope; but many other combinations of footwear, traction devices, poles, and self-arrest tools are commonly used. Conditions can rapidly improve or deteriorate and equipment can fail. Whatever combination of equipment is selected it’s important to understand its use and limitations.

After reaching an elevation of about 8000′, we stayed on the crest all the way to Mt. Hawkins (8850′) and the Mt. Hawkins lightning tree. The ridge route had the advantage of being mostly snow-free, but in places is quite rocky and steep. There are also a number of downed trees scattered across the ridge — vestiges of the 2002 Curve Fire.

In middle of Winter in 2014 there was so little snow on the PCT between Islip Saddle and Mt. Baden-Powell it was possible to run to Baden-Powell and back, do Mt. Hawkins, Throop Peak and Mt. Burnham along the way, and be back to Islip Saddle in the early afternoon. Not today. Winter’s storms had left more of the trail snow-covered than snow-free — and not with just a little snow.

A little beyond the Hawkins – Throop Peak saddle we stopped at a sunny, wind-protected spot with a nice view of Mt. Baldy for a few minutes, and then headed down. The snow conditions had improved considerably, and at one point we glissaded down a short slope.

It had been another outstanding day in the mountains, and I could only sigh, thinking of the many great days and experiences that Patty would have on the Pacific Crest Trail.