It had been a long time since I was on the summit of Santiago Peak (aka Saddleback). The last time was in 1975, when I flew from the peak on a Sunbird “Butterfly” hang glider. That day had been spectacular, and this was turning out to be a spectacular day as well.

In the throes of an El Niño Winter, Southern California had been pummeled by a series of Pacific storms. With all the rain and snow it seemed unlikely that the Twin Peaks 50/50 would be run as planned. But the key access roads didn’t wash out, most of the snow melted, and blue skies and great weather greeted runners race day morning.

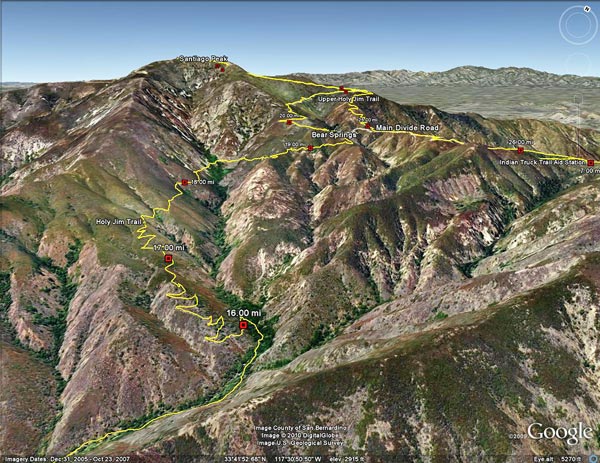

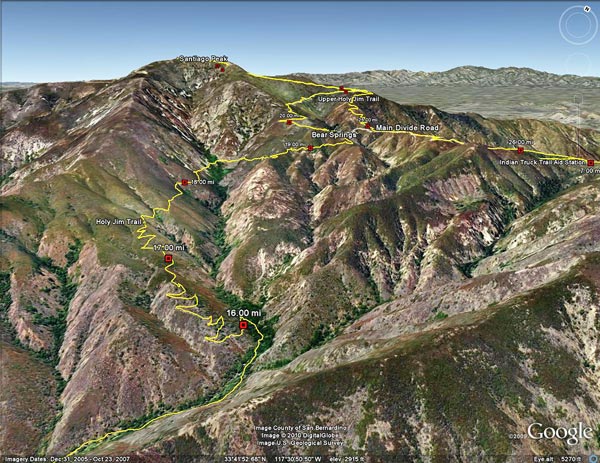

The race started at the bottom of Indian Truck Trail, off the I-15 near Corona. It was warm enough that in our 8:00 wave of 50K runners, only a few people wore sleeves and extra clothing. As we worked up the first switchbacks into the sun, those were quickly shed. The enthusiasm of the other runners was contagious, and this helped with the challenges of the initial 7 mile, 2600′ climb to the Indian Truck Trail aid station.

At that first aid station I grabbed a GU gel, and then headed east on the Main Divide Road toward West Horsethief. For some reason I had it in my head that I might get to run on the flat here for a few minutes. The only way that was going to happen is if I ran around the aid station table. On this course you’re either going up or you’re going down, and here the arrow still pointed up.

The views along the Main Divide were fantastic. The high peaks of Southern California — Mt. Baldy (10,064′), San Jacinto Peak (10,834′) and San Gorgonio Mountain (11,499′) — glistened in the morning sun, their new snow impossibly white. Down in the valley, an ant-like stream of vehicles moved along the Corona freeway, and our parked cars glittered like a string of tiny beads along Santiago Road. To my right, steep, chaparral covered slopes plunged into the depths of Trabuco and Holy Jim canyons. Somewhere down there was the Holy Jim aid station, and it looked like a long way down.

At the West Horsethief Trail aid station (10.2 mi), Billy and Lori greeted me with big smiles and asked if there was anything I needed. I had just been asking myself that same question, wondering if I had enough water to make it to Holy Jim. I guessed that I did, thanked them for being there, and turned down the single track trail.

Varied and technical, the West Horsethief and Trabuco trails were my favorite part of the course. While some sections were rocky, or V-rutted from recent rains, long stretches of of the trail were smooth and fast. Once down in the canyon, the creek crossings on the Trabuco Trail were great fun. With the warm weather, wet socks and squishing shoes were no big deal. The lush green growth and the burbling stream eased the long run down the canyon, and at about the 3 hour mark, I reached the Holy Jim aid station (14.5 mi).

This aid station is on the opposite side of the mountain from the start. You’ve done a lot of work to get there, and you’re going to do a lot more to get back. From here it is about 8 miles and a 3900′ gain to the summit of Santiago Peak. It took a while to work up past the cabins in Holy Jim Canyon to the start of the Holy Jim Trail. I knew I was on-route, but I hadn’t run any of these trails, and worried I might accidentally run up somebody’s long driveway.

As I climbed out on the first switchbacks above the creek, Hiroki Ishikawa, the eventual winner of the 50 mile race, rounded a switchback. Elite athletes stand out in any sport — there is a an efficiency and fluidity of movement that is unmistakable. Hiroki was quicksilver fast, and seemed to flow effortlessly down the trail.

In contrast, I felt a little like mud trying to flow uphill. Fortunately, long stretches of the trail were runnable, and ever so slowly I rose above Holy Jim Canyon. Gradually, the peak tops and rigelines that had been towering above me fell away. About 4.5 hours into the race, I reached the top of the Holy Jim Trail at Bear Springs, and turned left onto the Main Divide road.

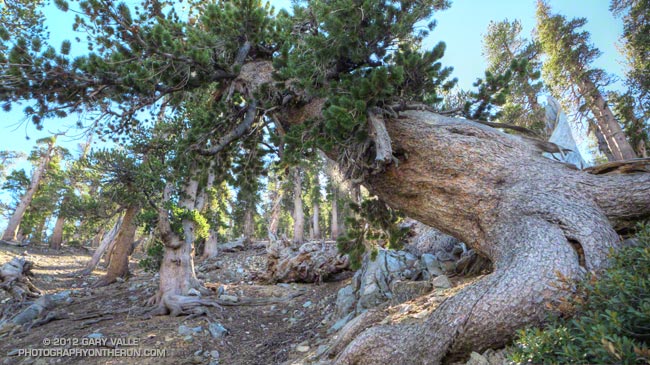

The surprising thing about this shady nook is that when you reach this point, you’ve only done a little more than half (56%) of the gain from Holy Jim to Santiago Peak. But hey, I was happy with that, and it felt good to be in the pines and plodding up toward the peak.

It took about 30 minutes to reach the big switchback at the Upper Holy Jim checkpoint (21.1 mi). From here the summit towers looked tantalizing close. I was happy to keep pace with the “runner in blue” about a hundred yards ahead. As we neared the top of the peak, sun turned to shade, and the road became covered with snow. It was a cool way to finish a warm climb, and a not so subtle reminder of what the weather might have been.

It took about 30 minutes to reach the big switchback at the Upper Holy Jim checkpoint (21.1 mi). From here the summit towers looked tantalizing close. I was happy to keep pace with the “runner in blue” about a hundred yards ahead. As we neared the top of the peak, sun turned to shade, and the road became covered with snow. It was a cool way to finish a warm climb, and a not so subtle reminder of what the weather might have been.

Leaving the top of Santiago Peak (22.6 mi) I thought back to that day in 1975. I wouldn’t be flying down the mountain today, with a hang glider or without. In its own way the 10 mile descent from the peak would be just as challenging as the climb up earlier in the day. But I wasn’t thinking about that. I was smiling and thinking that the running had been about as good as trail running gets.

Many thanks to RD Jessica DeLine, and all the volunteers and runners for an excellent event! Kudos to the 50 mile runners, who not only got to climb Santiago Peak via Holy Jim, but had the pleasure of running down Holy Jim and then climbing up West Horsethief and doing Santiago a second time.

Many thanks to RD Jessica DeLine, and all the volunteers and runners for an excellent event! Kudos to the 50 mile runners, who not only got to climb Santiago Peak via Holy Jim, but had the pleasure of running down Holy Jim and then climbing up West Horsethief and doing Santiago a second time.

Here’s an interactive Cesium browser View of the 50K course, and an elevation profile generated in SportTracks. Based on my GPS track, the distance worked out to a little over 33 miles, with an elevation gain of about 7600′. The elevation gain was hand calculated using SRTM corrected profile elevations. (For more info about measuring elevation gains on mountain trail runs, see the post What’s the Elevation Gain?)

When split times are available, you can learn a lot about how you, and others, ran the course. Everyone’s race is unique, and no one approach works the best. In the following listings, I’ve calculated the time from the start to each aid station, the time between aid stations, and the split rank at each aid station. These are totally unofficial. In a few places where a split time was invalid (for example earlier than a previous aid station) I’ve substituted estimated times. The “Rank” indicated is based on the time from the start to that point in the course. In both the 50K and 50M the top runners had missing splits, so for that split, they will not be included in the split rankings.

Here are the 50K Split Calculations and the 50M Split Calculations. If you want to send me your corrected or missing splits, I will update the listings when I have a chance. Please see the Twin Peaks 50/50 web site for official results and information.

It took about 30 minutes to reach the big switchback at the Upper Holy Jim checkpoint (21.1 mi). From here the summit towers looked tantalizing close. I was happy to keep pace with the “runner in blue” about a hundred yards ahead. As we neared the top of the peak, sun turned to shade, and the road became covered with snow. It was a cool way to finish a warm climb, and a not so subtle reminder of what the weather might have been.

It took about 30 minutes to reach the big switchback at the Upper Holy Jim checkpoint (21.1 mi). From here the summit towers looked tantalizing close. I was happy to keep pace with the “runner in blue” about a hundred yards ahead. As we neared the top of the peak, sun turned to shade, and the road became covered with snow. It was a cool way to finish a warm climb, and a not so subtle reminder of what the weather might have been. Many thanks to RD Jessica DeLine, and all the volunteers and runners for an excellent event! Kudos to the 50 mile runners, who not only got to climb Santiago Peak via Holy Jim, but had the pleasure of running down Holy Jim and then climbing up West Horsethief and doing Santiago a second time.

Many thanks to RD Jessica DeLine, and all the volunteers and runners for an excellent event! Kudos to the 50 mile runners, who not only got to climb Santiago Peak via Holy Jim, but had the pleasure of running down Holy Jim and then climbing up West Horsethief and doing Santiago a second time.