A valley oak burned in the 2005 Topanga Fire. From Wednesday afternoon’s sunset run.

A valley oak burned in the 2005 Topanga Fire. From Wednesday afternoon’s sunset run.

Did the Colby Canyon – Strawberry Peak – Red Box loop again over the Thanksgiving holidays. While taking some photos near Strawberry’s summit I was struck by the regrowth that has occurred since the 2009 Station Fire. What caught my eye were the bare limbs of the old growth, burned in the fire, projecting from the new, dense, green growth.

The growth of the chaparral over the seven years since the fire does not appear to have been noticeably impaired by the 2011-2015 drought in Southern California. (In the photograph above note the height of the regrowth compared to my friend near the summit.)

This conclusion is based in part on the observation of chaparral regrowth following other fires, such as the 2005 Topanga Fire, but is also supported by comparing the amount of new growth to the pre-Station Fire growth. This can be inferred by the length of the burned limbs and the approximate age of the chaparral when burned by the Station Fire.

According to the FRAP California geodatabase of fire perimeters, the last fire to burn the summit of Strawberry Peak was the 1979 Sage Fire, which burned approximately 30,000 acres. Before that you have to go back to 1896 to find another fire in the database that burned Strawberry’s summit.

In the absence of fire, it appears that in another 23 years the chaparral in the title photo could reach a similar height and extent to the old growth.

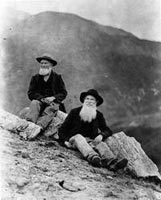

This photograph of Jason and Owen Brown (Los Angeles Public Library, Security Pacific National Bank Collection) is cataloged with the following description:

“Photo of Jason and Owen Brown, sons of John Brown of the Civil War and Abolition fame. View shows Jason and Owen Brown sitting on Mount Wilson, near the site of their cabin in 1884.”

Is the reference to Mt. Wilson accurate? Probably not. The peaks in the background establish they are not on top of Mt. Wilson. While they might be elsewhere on the mountain, it doesn’t seem likely. Mt. Wilson is more than five miles from their El Prieto cabin site. In his guidebook Trails of the Angeles, John Robinson describes the photo of the Browns as being “on Brown Mountain” — a peak which is near their El Prieto cabin, and which figured prominently in their lives.

Not having climbed Brown Mountain, I was curious to see if the photo of the “Brown Boys” was taken on or near its summit. Early this morning I set off from Red Box, Brown Boys photo in my pack, to do a loop through Bear Canyon and Arroyo Seco, and take a side trip to Brown Mountain along the way.

The detour to Brown Mountain began at Tom Sloan Saddle and followed the peak’s east ridge over several false summits to the summit of the peak. Brown Mountain’s rounded summit sits on the divide between Bear and Millard Canyons and on a clear day affords a panoramic view of the surrounding mountains and much of the Los Angeles area. Big views can lead to big dreams, and according to an article in the Los Angeles Herald in October 1896, the Boys had planned to build an observatory on the peak. While this was not built, the Boys did succeed in having the peak named in honor of their father

On the summit, and with the Brown Boy’s photo in hand, I faced first north over Bear Canyon, then east toward Mt. Disappointment, San Gabriel Peak and Mt. Markham; and finally south over Millard Canyon. Neither the terrain or skyline matched the photograph.

The best match I’d found today was on a peaklet near Tom Sloan Saddle looking southeast toward Inspiration Point. More likely the photo was taken on a ridge closer to their cabin. That adventure would have to wait for another day. Today the clock was ticking and I needed to retrace my steps back to Tom Sloan Saddle, descend Bear Canyon and then follow the Gabrieleno Trail up Arroyo Seco and back to Red Box.

Some related posts: Bear Canyon Loop Plus Strawberry Peak, Red Box – Bear Canyon Loop, Arroyo Seco Sedimentation

Following are a few photos taken along the way. Click a tile for a larger image and additional information.

Each time I’ve run the segment of the Pacific Crest Trail between Inspiration Point and Vincent Gap I’ve been curious about a cluster of young pines in a burned area near Grassy Hollow. The trees appear to be older than similar areas of regrowth along the PCT between Mt. Baden-Powell and Little Jimmy Spring, which burned in the 2002 Curve Fire.

In turns out the area near Grassy Hollow was burned in the 18,186 acre Narrows Fire in 1997. That would make these trees about five years older than the Curve Fire regrowth.

Considering our huge precipitation deficit in Southern California over the past five years, the young trees in the Curve and Narrows fire areas seem to be doing surprisingly well.

It’s been more than six and a half years since the devastating Station Fire burned 160,577 acres in Angeles National Forest.

The pine seedling above is on the Three Points – Mt. Waterman trail (10W04) in an area burned by the Station Fire. It’s 3.5 miles from Three Points and at an elevation of about 7000′. It’s about three years old.

How long will the seedling have to grow to replace the mature trees lost in the fire?

A couple more miles up the trail, near the Twin Peaks Trail junction, is a Jeffrey pine burned by the Station Fire and then cut by fire fighters. The tree is representative of the mature trees in this area of the forest. An inexact, but conservative, count of its growth rings is in the neighborhood of 325.

So the burned tree was a seedling sometime around 1690. If the seedling survives the drought, increasing temperatures, subsequent fires and droughts, and other maladies that can befall a tree, it will reach the age of the burned tree around 2340.

Here’s hoping that it does, and that the forests will be as enjoyable then as they are now…

Update August 4, 2020. In July 2018 a count of the tree rings of a large Jeffrey pine cleared from the Three Points – Mt. Waterman Trail revealed approximately 500 rings!

Some related posts: Lemon Lily Along the Mt. Waterman Trail, After the Station Fire: Three Points – Mt. Waterman Loop, Three Points Loop Plus Mt. Waterman

Since kayaking Arroyo Seco with Gary Gunder during the 1997-1998 El Nino, I’ve enjoyed revisiting the many drops and falls along Arroyo Seco when running in the area.

When we did the Bear Canyon loop a couple of weeks ago, I was amazed to see many of Arroyo Seco’s stream features were nearly filled in with sediment. This image comparison shows a drop below Switzer Falls in March 2012 and in March 2016.

Doing a little sleuthing using Yelp reviews of Switzer Falls, it looks like the creek had low sediment levels in early January 2014, but was heavily silted in mid-March 2014. Based on this, it appears that the initial sedimentation event occurred during the storms of February 26 – March 2, 2014, when nearby Opids Camp recorded 10.95 inches of rain.

The origin of the 2009 Station Fire was in the Arroyo Seco watershed and it was one of the most severely impacted. A question that comes to mind is why did the Arroyo Seco drainage produce such a high rate of stream sedimentation in the February-March 2014 rain event, but not in the very high flows of February 2010 and December 2010, and the moderately high flows of March 2011?

Some of the factors likely include vegetative cover, rainfall rate, recent rainfall history, the soil’s hydrophobicity, the soil support provided by degrading root systems, the magnitude of the peak flow and the shape of the stream discharge curve. Our multi-year drought has been an amplifying factor, further reducing vegetative cover and soil support.

For more information regarding the history of the Arroyo Seco watershed and plans for its rehabilitation see the Arroyo Seco Foundation web site.