Twin Peaks (East) from the Mt. Waterman Trail

Today was the first chance I had had to run the recently reopened stretch of the Pacific Crest Trail between Three Points and Cloudburst Summit. Originally within the Station Fire closure area, this segment of trail was reopened when the size of the closure area was reduced in late May. In addition to checking this section of the PCT, I also wanted to see the condition of the forest and trail at the current closure boundary near Mt. Waterman.

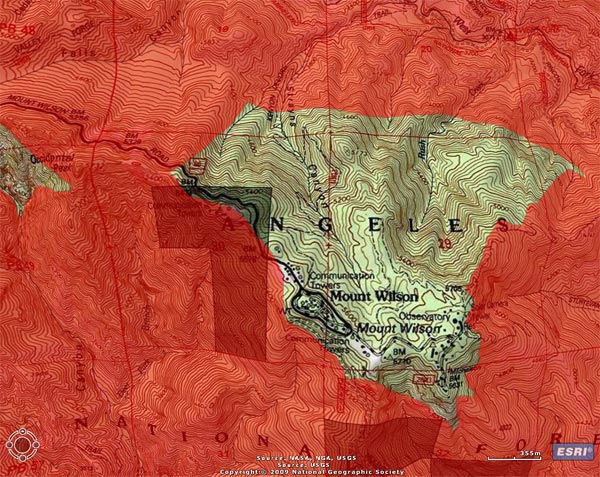

Between Three Points and Cloudburst Summit, the PCT generally parallels Angeles Crest Highway (Hwy 2), and crosses the highway several times. In general, the burn severity along the trail appeared to match the burn severity depicted in the NASA Ikhana BAER image and Angeles National Forest BAER Station Fire Soil Burn Severity Map. In the first two miles some trees were lost, but much of the forest in the immediate vicinity of the trail did not appear to be severely burned.

That was not the case about a half mile west of Camp Glenwood, where the PCT crosses Hwy 2 and climbs up a hill. Here the burn severity was much higher, and most of the trees were killed. The trail was in good shape and it didn’t take long to get through this section and back into the unburned forest. Remarkably, Camp Glenwood was unscathed.

The remaining 3 miles to Cloudburst Summit were not burned. Some trail work had been done on this stretch, as well as down in Cooper Canyon. As always, the running through Cooper Canyon was superb. At the PCT’s junction with the Burkhart Trail, I turned right and climbed up to Buckhorn Campground, and then followed the camp entrance road up to Hwy 2. From here it was a short jog west to the Mt. Waterman Trail.

Most of the forest of Jeffrey pine and incense cedar on the east side of Mt. Waterman was outside of the fire area, and it wasn’t until near the junction with trail 10W04, that some damage from the fire could be seen. It looked like spot fires had run up the mountain, burning primarily in the understory. The north face of Twin Peaks, across from Mt. Waterman, appeared to be unaffected by the fire.

It is unclear why the Forest Service chose to define the updated Station Fire closure area (Forest Order No. 01-10-02) so that the trail to Twin Peaks remains closed. Based on the Forest Service’s own BAER report, the burn severity down to Twin Peaks Saddle is generally categorized as low to very low/unburned, and the north face of Twin Peaks is outside of the burn area.

Some related posts: Cooper Canyon Cascade & Falls, Mt. Wilson Area Peaks From Twin Peaks