A hiker contemplates the day from the front steps of Mt. Baldy’s San Antonio Ski Hut.

From Sunday’s Back to Baldy trail run.

A hiker contemplates the day from the front steps of Mt. Baldy’s San Antonio Ski Hut.

From Sunday’s Back to Baldy trail run.

Today was the first chance I’d had to get back to Mt. Baldy since the Run to the Top was called 45 minutes into the race on Labor Day. Thunderstorms were the problem that day, but not today. The waning moon was the only blotch of white in the cloudless sky, and it wasn’t going to cause any weather problems.

Part one of the plan for today’s run/hike was to do a “run to the top” of Baldy using the ski hut trail. That would help make up for the incomplete race on Labor Day. Part two was to do some peakbagging and climb West Baldy, Mt. Harwood, Thunder Mountain and Telegraph Peak. Relatively close together, these peaks can be done as part of an 18 mile adventure, with an elevation gain and loss of about 6000′.

Climbing Baldy via the ski hut trail is about three miles shorter than the Run to the Top route via the Notch, but takes me about the same amount of time. Ultimately it’s the rate of climb that can be sustained that determines your speed up the peak, and the elevation gain by either route is about 3900′. The ski hut trail can be busy, but I enjoy climbing the peak by this route. The tradeoff is that it is steeper and is less runnable.

Without some weather to stir things up, the views from the summit of Mt. Baldy were a little hazy, but San Gorgonio and San Jacinto could still be seen off to the east, Saddleback to the south, and Mt. Baden-Powell and other peaks of the San Gabriels to the northwest. I could also see Telegraph Peak sitting behind Thunder Mountain, and wondered how the trail between them was going to be.

After doing the half-mile jog over to West Baldy, I returned to the summit of Baldy and descended to the Baldy-Harwood saddle. Mt. Harwood is another one of those peaks I’ve run past many times. Harwood sees far fewer ascents than Baldy, but enough so that a path has developed from the Baldy-Harwood saddle up its broad west ridge. Today, save a a red-tailed hawk cruising by, its summit was empty.

Continuing along Harwood’s elongated summit, I began to work down the peak’s east ridge, staying on its crest. The east ridge is steeper and much less traveled than the west ridge. It is an extension of the Devil’s Backbone and its north side is a steep, crumbly precipice that drops more than 3000′ to Stockton Flat. The views along the ridge are excellent, but some care is required.

The east ridge of Mt. Harwood rejoined the trail at the Devil’s Backbone. From there it took about 15-20 minutes to run down to (just above) the Notch and start up the service road that leads past the new snow making reservoir to the top of Thunder Mountain. I’d been to the top of Thunder several times and by several means — by ski lift, by mountain bike, and by foot during the Baldy Peaks 50K. In that race Thunder had been the final challenge after climbing Mt. Baldy twice — once from the village and once from Manker Flat.

Maybe because of pushing the pace on the ski hut trail, I was pretty worked going up the road to Thunder, and wondered if I was going to be able to make it to Telegraph Peak before my loosely set turnaround time of noon. I’d hoped to get back down to the car and on the road by around 1:30 pm, and felt like I was running a little behind.

But Telegraph is a compelling peak, particularly when viewed from the northwest, and from Thunder Mountain it only took about 30 minutes on the Three Tee’s Trail to get to its summit. In another 30 minutes I was back at Thunder Mountain, and looking forward to the five miles of downhill that would take me back to the car.

Related post: Mt. Baldy Run (Part Way) to the Top 2011

A run or hike doesn’t have to be long or difficult to be enjoyable! It had been a while since I’d done San Gabriel Peak, Mt. Markham, and Mt. Lowe; and although I’d run within a quarter-mile of the summit of Mt. Disappointment several times, I’d never done the last bit up to the peak. All four of these peaks can be done in a (round trip) run/hike of less than ten miles, with a cumulative elevation gain/loss of around 3000′.

Depending on where you prefer to park, the run/hike can start at the San Gabriel Peak Trail trailhead, which is about one-third of a mile up the Mt. Wilson Road, or at Red Box on Angeles Crest Highway. Parking at Red Box requires running/hiking on Mt. Wilson Road to the trailhead.

The San Gabriel Peak/Mt. Disappointment trail climbs up through a forest of chaparral, canyon live oak, and Bigcone Douglas-fir about 1 1/2 miles to the Mt. Disappointment road, just below the antennae-infested summit of the peak. Along the way there are great views of the canyon of the West Fork San Gabriel River and San Gabriel Peak. The paved road is followed south (left) to a sharp switchback and then a short distance up to the top of Mt. Disappointment (~ Mile 2.1).

In Trails of the Angeles, John Robinson describes how government surveyors lugged their equipment to the top of Mt. Disappointment in 1875, only to discover that another peak to the southeast was higher. That peak was San Gabriel Peak. Except for Strawberry Peak (6164′), San Gabriel Peak (6161′) is the highest of the front range peaks. It is the most prominent peak on the eastern skyline when viewed from the San Fernando Valley, and is sometimes mistaken for Mt. Wilson.

I imagine it was a bit easier for me to get over to San Gabriel Peak than for the surveyors when they did the peak’s first ascent. All I had to do was run a third of a mile down a paved road and pick up the San Gabriel Peak Trail on the southeast corner of the switchback. The trail up to San Gabriel Peak forks to the left off the trail to Markham Saddle about a tenth of a mile from the switchback.

The divide extending from Mt. Disappointment to Mt. Wilson was the approximate boundary of the Station Fire in this area. Although the summit of San Gabriel Peak burned, much of the northeast side of San Gabriel Peak and Mt. Disappointment did not. From what I can determine, the northeast side of these peaks last burned in the 1898 “Mt. Lowe” fire. There’s a nice section of trail just below the summit of San Gabriel Peak that passes through a corner of Bigcone Douglas-fir forest that was not consumed by the Station Fire.

After enjoying the panoramic view from the top of San Gabriel Peak (~ Mile 2.9), I retraced my steps back down to the “main” trail and continued to descend to Markham Saddle and the Mt. Lowe fire road. At this point another trail begins on the Mt. Markham side of the road. This trail leads southwest to a saddle between Mt. Markham and Mt. Lowe. Mt. Lowe Road is closed between Markham Saddle and Eaton Saddle because an active rock slide destroyed the road just west of Mueller Tunnel.

From the Markham-Lowe saddle a path follows the southwest ridge of Mt. Markham about a half-mile to its summit. The route up the ridge is relatively straightforward, but a steeper section requires a little scrambling over fractured, loose rock. The high point on Mt. Markham’s elongated summit ridge appeared to be a pile of rocks covered with Turricula. A little further out on the ridge was a clearing with a rusty can that may have been a summit register (~ Mile 5.1).

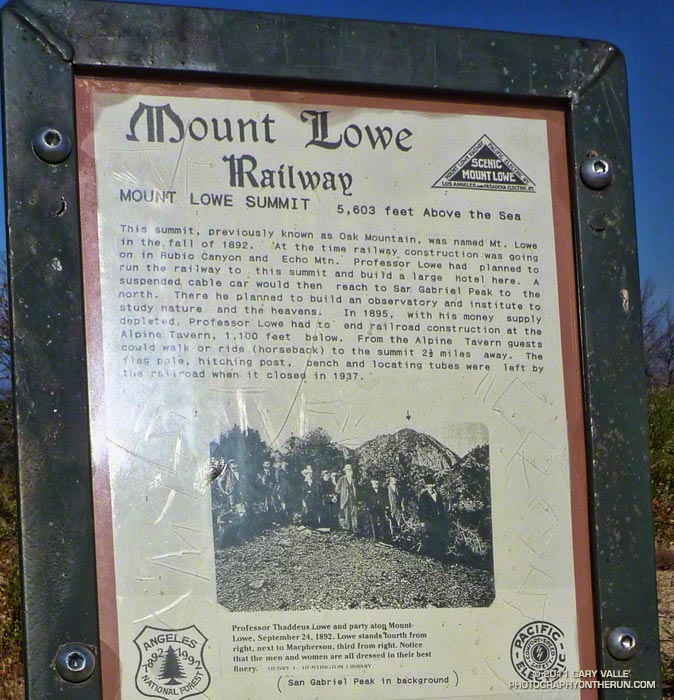

Returning to the Markham-Lowe saddle, less than a half-mile of moderate uphill led to the summit of Mt. Lowe (~ Mile 6.0). There’s a bench here, along with locating tubes pointed at various landmarks. As explained by the interpretive sign on the peak, Professor Thaddeus Lowe had planned to build a large hotel on the summit, serviced by the Mt. Lowe Railway. In his grand vision, a suspended cable car would have continued to San Gabriel Peak, where an observatory was to be built. Here’s a map of Mt. Lowe area trails and landmarks created by The Scenic Mt. Lowe Railway Historical Committee.

It was on the way back, near Mt. Disappointment, that I heard and saw the F-18s described in So Many Heroes. It turns out the fighters had done a flyover as part of a 9/11 Memorial dedication in Pasadena.

Turricula (Poodle-dog bush) Update

Turricula was present virtually everywhere along the route that had been burned, and could not entirely be avoided. It was especially prevalent on the path to summit of Mt. Markham from the Markham-Lowe Saddle.

I’ve been exposed to Turricula now on a number of runs, and except for the first time, when I literally waded through unbroken stands of the sticky young plants, it hasn’t been a problem — even wearing running shorts and short-sleeves. I’ve had a little irritation on my ankles, or sometimes along my waistband, or a random spot here or there, but it’s been no big deal. Certainly nothing like the widespread inflammation, swelling and blisters the first time!

Of course now I at least make an attempt to avoid the plants. And I also wash off my arms and legs at the earliest opportunity after being exposed to Turricula.

It also seems the older plants don’t have as much of the “exudate” on them, since my legs and arms haven’t become sticky from brushing up against the plants. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in the older plants irritation results from the almost microscopic hairs on the plant. It is thought these irritating hairs are more easily broken and shed as the plant ages.

Somewhere around the junction of the 210 and 605 I saw a flash of lightning to the south. As if the flash had been a warning, a gust of wind buffeted my car, and a blizzard of dust and debris blew across the freeway. Then it started to rain. Not good — especially when you’re on your way to a race that ends on top of a 10,000′ mountain.

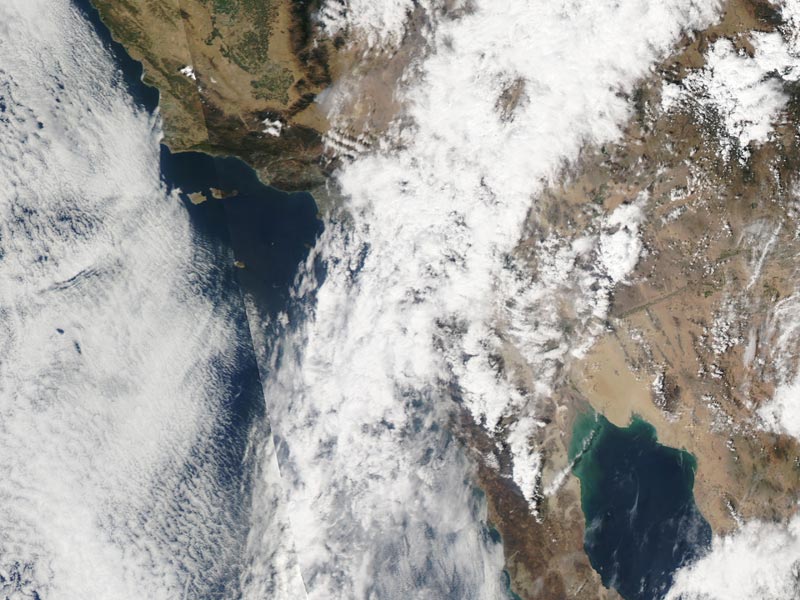

A complicated weather scenario had developed for race day. A very moist layer of monsoonal moisture had been pushed up into Southern California from Baja by a combination of a weak upper level trough off the coast and big upper level high over Four Corners. A combination of factors including an unseasonably strong jet stream had helped trigger a band of showers and thunderstorms that extended from west-southwest off the coast, across the Los Angeles basin, and into the San Gabriel Mountains.

When I drove into the Mt. Baldy Ski Lifts parking lot at around 6:45 am it was raining hard enough I didn’t want to get out of the car. Procrastinating, I went through the admittedly optimistic ritual of applying sun screen. After a few minutes the rain tapered off to sprinkles and I walked down to the Start Line to pick up my bib. The word was conditions were improving and it looked like we were going to be able to get in the race.

Each year the Baldy Run to the Top attracts 500 to 600 runners. Some are the best of the best and will run the seven miles and nearly 4000′ of elevation gain in under 75 minutes. About two-thirds of the runners usually finish in around 2:15 or less.. A few just want to give it a go and soon find that climbing the rough equivalent of 6500 stairs — at altitude — is more than they bargained for.

Usually the weather is pretty good — some years are a little warmer or cooler, or have a few more clouds than others, but blue skies and sunshine are the norm, and significant rain — or lightning — usually isn’t a problem.

It was deceivingly warm as runners gathered at the start line. The wind chill on top was reported to be a chilly 38 degrees. A few runners had on extra clothing, and a number of runners had an extra top or shell tied around their waste. Some had extra gear stuffed in their packs, but a few — including a couple of shirtless runners — had nothing to combat the weather.

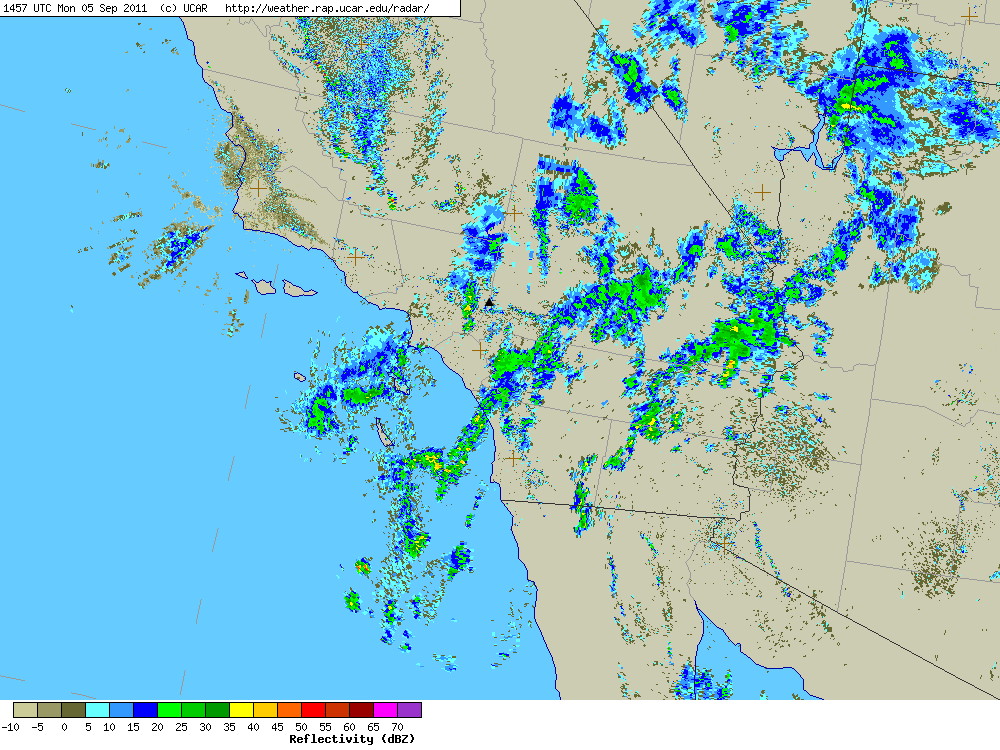

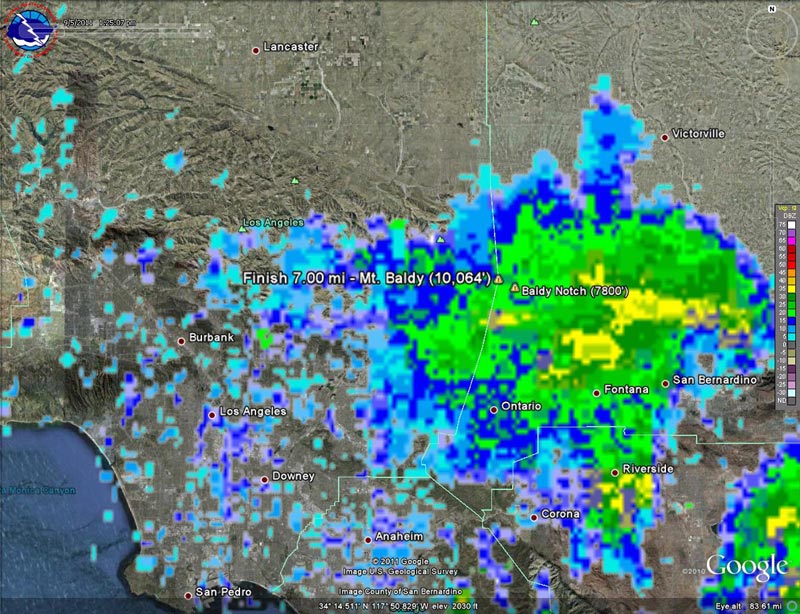

Here’s a UCAR regional NEXRAD composite radar image from about 8:00 am. The approximate location of Mt. Baldy is marked by a black triangle near the center of the image. (Note that radars in the region vary in how they show a particular area and that a cell may be stronger than indicated in the composite. Also there’s some “clutter” in the image that isn’t necessarily rain.)

With what sounded like a more reserved “3… 2… 1… GO!” the race started and pounded down the wet pavement to Manker Flats (6160′), where it turned up the ski area service road. The (mostly) dirt road would take us to the Notch (7800′) and then the top of Chair 4 (8600′). From there a trail would take us across the exposed Devil’s Backbone, then across the south face of Mt. Harwood, and on to the final gut-wrenching 700′ climb to the summit of Mt. Baldy (10,064′). Here’s an interactive Cesium browser View of the race course.

The weather on the way up to the Notch was a little unsettled, but great for running. There was a mix of clouds and sun, and even a brief shower, but overall it looked like the weather might be improving.

Just before rounding the last switchback up to the Notch, a runner with a bib was running down. This was odd because he was running well. Why would he have quit the race? Running up to the aid station at the Notch I still hadn’t caught on, and was wondering why so many people were standing around at the aid station.

That’s when I learned that about 45 minutes into the race, on the recommendation of SAR officials, the race had been shut down. I’m not sure what the “final straw” was but would guess it was nearby thunderstorms and perhaps a growing concern that rain and wind associated with a rapidly developing cell could cause serious problems for runners not prepared for inclement weather.

Here’s what a regional composite radar image looked like at around 9:00 am, and then just one hour later, as a “train” of cells about 20 miles from Mt. Baldy continued to develop and stream into the San Bernardino Mountains in the area of Silverwood Lake, Crestline and Lake Arrowhead.

Lightning was not only a risk for runners, but for the 50+ SAR and fire personnel spread across the mountain, and the 25+ volunteers that would be on top of the mountain for the duration of the event.

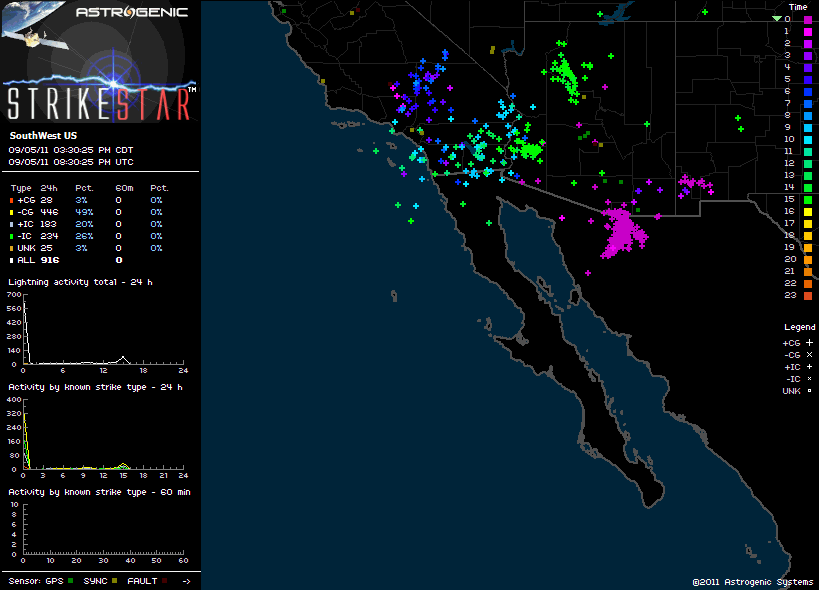

There was lightning in the area. We saw it driving to the race and I heard at least one clap of thunder while warming up before the race. Here’s an image of Astrogenic StrikeStar lightning detections in the southwestern U.S. from 10:00 pm PDT Sunday to about 1:30 pm PDT race day. Note the high percentage of cloud-ground strokes.

As this composite radar loop from WSI Intellicast.com shows, bands of showers and thunderstorms streamed into the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains most of Labor Day. Cells were moving relatively rapidly and developing over a wide swath that extended from west of Mt. Baldy south and east to San Diego and Palm Springs. (Mt. Baldy is just north of ONT on the radar map.)

It was pretty much a crapshoot where a particular cell would develop, how strong it would be, and what its extent would be. This regional radar image shows a cell that moved into the Baldy area around 1:00 pm, and this Google Earth/NEXRAD image shows the same cell in relation to Mt. Baldy at around 1:30 pm.

As frustrated as I was to stop at the Notch, I don’t think there’s any question that officials made the right decision when they shut down the race. And I think most runners understand that it’s not whether a particular runner was able to make it up to the summit and back down OK, but what could have happened with several hundred people on the mountain and an ever-so-slight change in that wavering stream of heavy showers and thunderstorms.

Some related posts: Thunderstorm, Mt. Baldy Run to the Top 2009, Mt. Baldy Run to the Top 2007

Runners on Edison Road During a Recent Training Run

Note: The Mt. Disappointment Endurance Run is now the Angeles National Forest Trail Race.

No matter if you run at the front, middle, or back of the pack, there’s the race you plan, and the race you run.

Based on the course info, it looked like the 7th edition of the Mt. Disappointment 50K was going to be more difficult than in 2009 and 2010, adding both mileage and elevation gain. Because of the closure of Mueller Tunnel and the damage done by the Station Fire and subsequent floods, we still wouldn’t be running up and over the shoulder of Mt. Disappointment, or down to Clear Creek and around Strawberry Peak, but the 2011 course would make up for that with its own very memorable sections.

To try and cope with the difficulties of the course, I’d put in extra miles and done more back to back Saturday-Sunday runs. But in one of those uh-oh moments a couple of miles into the race, I could feel in my legs that I was probably going to need to adjust my expectations. I wasn’t injured. I wasn’t getting over a cold or flu. My stomach wasn’t upset. I felt pretty good. But there was this nagging bit of fatigue in my legs…

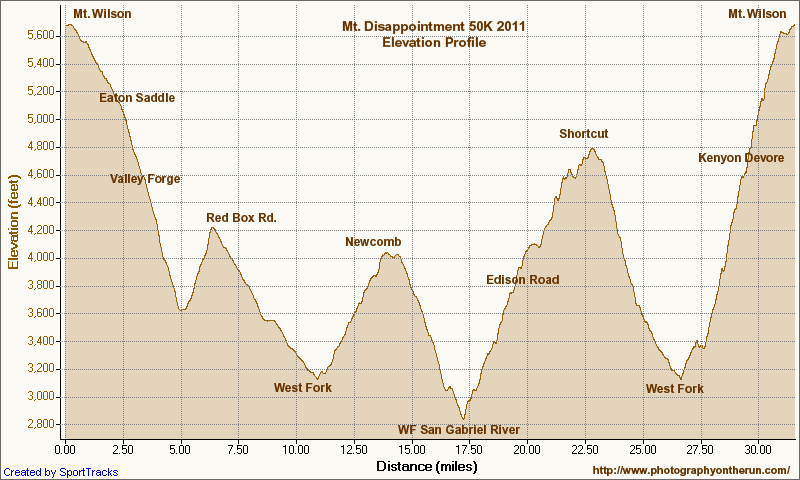

The new wrinkle for 2011 was that we turned off Mt. Wilson Road half-way to Red Box and ran down the Valley Forge Trail. In a training run a few weeks before the race, the Valley Forge Trail had been an obstacle course overgrown with Turricula (Poodle-dog bush). Trail work by Hilliard, Rowlan & Company had restored the trail, and today it was in great shape. Here’s an interactive Cesium browser View of the 2011 course and the courses in previous years, and an elevation profile of the 2011 course.

At the bottom of the Valley Forge we turned onto the Gabrielino Trail, and started up the canyon of the West Fork toward Red Box-Rincon Road. The change in grade from level to uphill confirmed it. I stepped aside so two running friends could pass. Maybe it was a tapering or over-training issue, or maybe it was just “one of those days.” Whatever, the legs were just not cooperating.

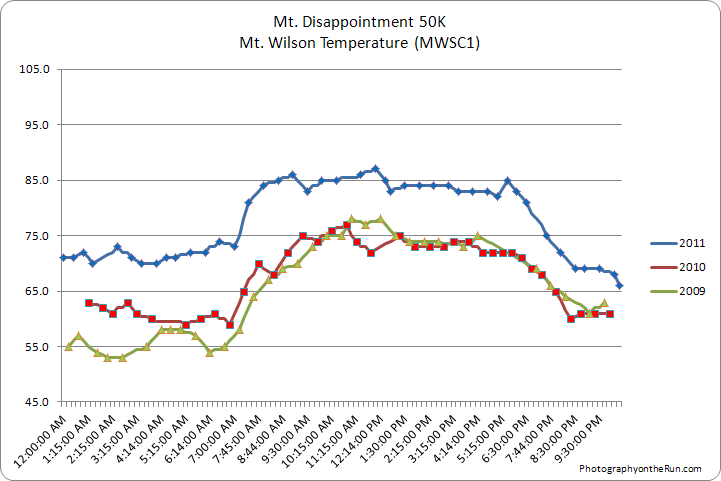

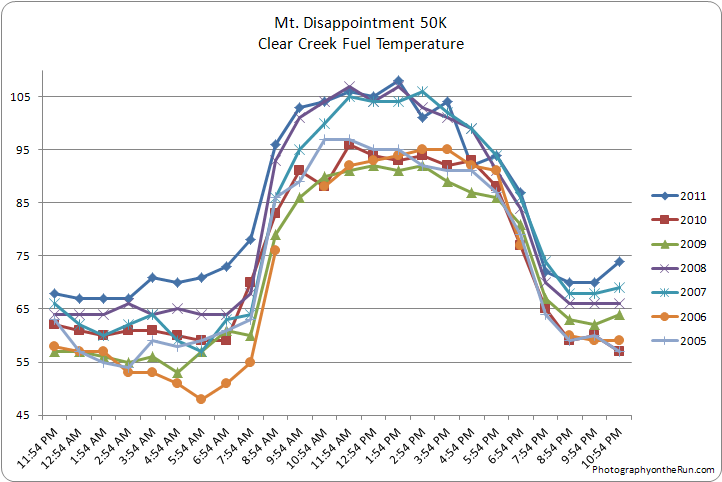

The irony is, this was probably a good thing. The day turned out to be the hottest of any Mt. Disappointment race to date. The lurking leg fatigue forced me to not push the pace, which made dealing with the temperature easier.

And hot it was! The forecast had looked decent just two days before the race, but Friday temperatures exploded in the mountains, jumping 10-12 degrees in 24 hours. The hot temps on Friday carried over into Saturday, making race day just that much warmer.

Here are the race day temperatures at Clear Creek and Chilao for 2005-2011, and Mt. Wilson for 2009-2011. And these temps are the temperature off the ground and in the shade! A better indication of the temperature in the sun is the “fuel temperature.” This is the temperature of a ponderosa pine dowel in direct sun. Here are plots of the race day fuel temperature at Clear Creek and Chilao for 2005-2011.

Because I wasn’t pushing the pace I didn’t hesitate to take a little extra time at aid stations. I can still feel that ice cold sponge on the back of my neck, and the cold water running down my back. This year there were numerous small stream crossings, and I think there was at least one small stream between every aid station. This was “free” cooling, and I paused a dozen times to dump water over my head. Thanks to the West Fork San Gabriel River, I was soaked from head to toe for the first steep, sun-baked section of Edison Road. This was also the case on the Silver Moccasin Trail in Shortcut Canyon and on part of Kenyon Devore.

Hot day or not there were some remarkable performances. Heather Fuhr was not only was the first place woman, she was fourth overall and set a new women’s course record of 5:07:11. Perennial favorite Jorge Pacheco sped through the tough Mt. Disappointment course in 4:46:29, winning the overall and setting a new course record in the Men’s 40-49 Division.

Once again the event was superbly organized by race director Gary Hilliard and the Mt. Disappointment 50K Staff, with the help of an extraordinary group of volunteers, runners, SAR personnel and sponsors. Thank you!

Related post: Mt. Disappointment 50K 2010 Notes

Poodle-dog bush* sprouting at the junction of the PCT and Mt. Waterman Trails, near Three Points.

Little plants like these can grow to be monster-sized, like these along Edison Road, below Shortcut Saddle.

The title photo was taken on a run around Mt. Waterman from Three Points on May 29, 2011 and the photo of the monster-sized Poodle-dog bush was taken on a Mt. Disappointment 50K training run from Shortcut Saddle on July 31, 2011.

*The taxonomic name for Turricula parryi (Poodle-dog bush) has changed to Eriodictyon parryi. The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition (2012) has returned Turricula to the genus Eriodictyon, as originally described by Gray. According to the Wikipedia entry for Turricula (April 11, 2012), “… molecular phylogenetic analysis carried out by Ferguson (1998) confirms that Turricula should be treated as a separate genus within a clade (Ferguson does not use the term “subfamily”) that includes Eriodictyon, and also the genera Nama and Wigandia; Eriodictyon is the genus to which Turricula is closest in molecular terms, and is its sister taxon.” I use “Turricula” and “Poodle-dog bush” interchangeably as a common name.

Related posts: Contact Dermatitis from Eriodictyon parryi – Poodle-dog Bush, Getting Over Poodle-dog Bush Dermatitis, Trail Runners Describe Reactions to Poodle-dog Bush