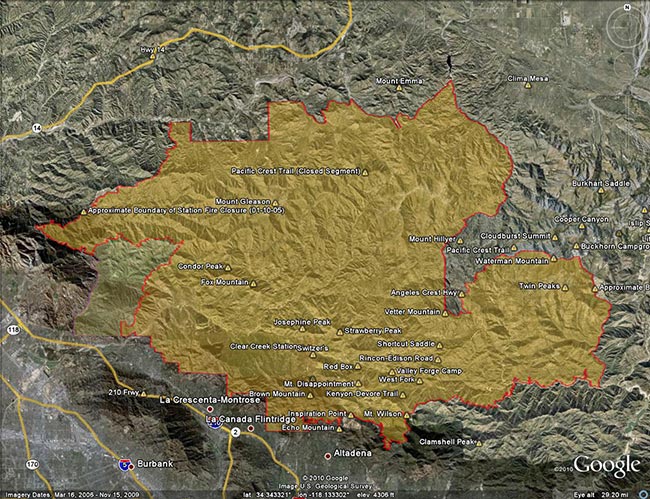

Update Friday, May 13, 2011. Good news! Effective Monday, May 16, 2011, Angeles National Forest is reopening about half of the area of the Forest currently closed as a result of the Station Fire. This reduces the closure area from 186,318 acres to 88,411 acres, and opens most of the burn area south and east of Angeles Crest Highway (Hwy 2) from Bear Canyon east to Twin Peaks. Some of the trails and areas opened are the Sunset Ridge Trail, Bear Canyon Trail, segments of the Gabrielino Trail, Nature’s Canteen Trail, San Gabriel Peak and Mt. Disappointment, Valley Forge Trail, Kenyon DeVore Trail, Silver Moccasin Trail, Pacific Crest Trail (some rerouting), Twin Peaks and the Mt. Waterman-Twin Peaks Trail from Three Points. For more information see the news release, detailed map, and other information related to Closure Order No. 01-11-03 on the Angeles National Forest web site.

On September 20th, after issuing a press release with the title, “Angeles National Forest reopens areas offering hiking, picnicking,” Angeles National Forest (ANF) reopened about 5 percent of the Station Fire closure area, and extended the closure of the remaining 186,320 acres another year to September 19, 2011. Here’s an ANF map of the revised closure area (PDF).

According to the press release, most of the areas burned in the Station Fire remain closed “for public safety.” When will these areas reopen? In the press release former ANF forest supervisor Jody Noiron states, “The Forest Service intent is to reopen areas severely damaged in the fire over the next few years as conditions allow.”

It’s hard to understand the rationale for the extent and duration of this closure. Over the past year, many dedicated forest users have participated in permitted work parties and events in the closure area. We’ve been on the trails and roads. We know firsthand that many miles of trails and dirt roads are passable, and much of the closure area could reasonably be in use.

Remarkably, a year after the fire, the size of the Station Fire closure area remains LARGER than the area burned by the fire! Some areas in the Forest that were burned are open, and some large areas that did not burn are closed.

Other than the boilerplate “to protect natural resources and provide for public safety” in the closure order, and some bureaucratic arm-waving, there has been very little information released documenting why these areas of ANF should remain closed.

According to an article posted on the Pasadena Star News web site (08/22/10 by Beige Luciano-Adams), acting ANF forest supervisor Marty Dumpis said, “It’s not just safety but also we have to allow the area to recover because if we allow people to start trampling over regrowth then they’ve just set it back another year. We hope people will be patient enough, allow natural recovery to begin, and then we can get some of these areas open.”

Is that the way Angeles National Forest higher-ups see us? The hikers, runners, and riders that most frequently use these trails are among the most experienced that visit the Forest. Trails constrain use, and are a minuscule part of the recovery area. If credible evidence exists that trail use would delay the area’s fire recovery, Angeles National Forest should make it available to the public.

To keep such a large area of public land closed for such an extended period following a Southern California fire is unprecedented. Even in the case of the largest Southern California fires, the Cedar and Zaca fires, closed areas in Cleveland and Los Padres National Forests were reopened within a year of the fire. In many cases fire closures in the National Forests of California have been lifted within days or weeks of a large fire. This reflects a general policy that closures be implemented and maintained as a last resort.

In a 2009 presentation following the Station Fire, Jody Noiren noted that Angeles National Forest:

– provides 72% of all open space in Los Angeles County

– has 17 million people living and working within 1 hour drive

– has 3.5 million visitors per year, of which half come from within a 50 mile radius of the Forest

It may simplify forest management, and be more convenient for the Forest Service to keep such a large area of Angeles National Forest closed, but it is clearly not in the public interest. Extending the Station Fire closure will not enhance recovery, increase protection of sensitive species, or prevent the spread of invasive plants. But it will deprive millions of people living and working nearby of an indispensable and intrinsic public resource.

Long experience in Southern California demonstrates that public lands can be reopened in a timely fashion following a fire without abusing resources, or putting the public in undue peril. It is time to stop the doublespeak and reopen all but the most severely damaged areas of the Station Fire burn area to public use.

The Station Fire closure area is in the congressional districts of Rep. David Dreier [R-CA26] and Rep. Howard McKeon [R-CA25]. California’s senators are Sen. Barbara Boxer [D-CA] and Sen. Dianne Feinstein [D-CA]. Determine and contact your Representative and Senators.