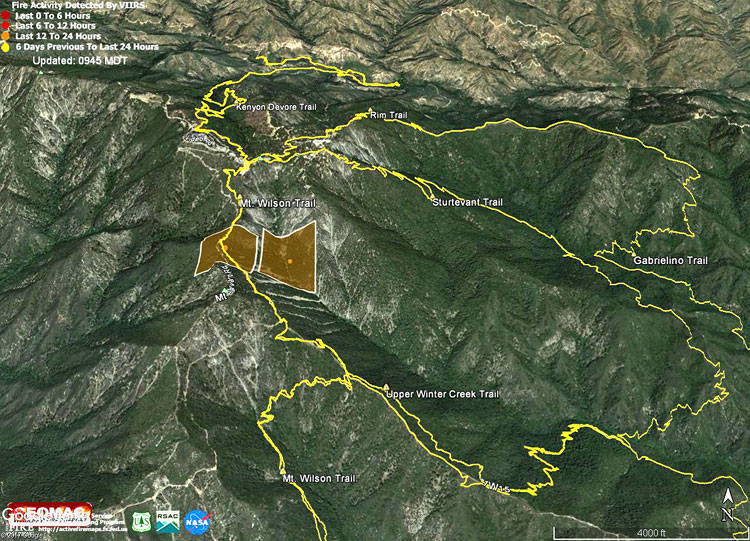

Update July 20, 2020. Here’s a Google Earth image of a CZU August Lightning Complex Fire perimeter from the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). The date and time of the perimeter is indicated. My GPS track from the PCTR Skyline to the Sea Marathon in Castle Rock and Big Basin Redwoods State Parks is also shown. The locations of all placemarks and trails are approximate. For official information see the CAL FIRE CZU August Lightning Complex and InciWeb CZU August Lightning Complex incident pages.

There’s a reason that Skyline to the Sea is Pacific Coast Trail Run’s biggest event. Close your eyes and picture your ideal trail. The trail of your dreams might be hard-pressed to match the appeal of the Skyline to Sea Trail.

There is something magical about running in an old-growth redwood forest. Established in 1902, Big Basin Redwoods State Park was the first state park in California. It’s redwoods reach 2000 years in age, 328 feet in height and 18.5 feet in width!

The Skyline to the Sea Trail has a net elevation loss, but enough uphill to get your attention. Many miles of the trail are as smooth as a carpet, but some are rocky, root-strewn and technical. It is often cool under the dense forest canopy, but it can also be warm and humid. I was surprised to see an “Emergency Water” stash a mile before the last aid station. In some years it is well-used and much appreciated.

The Park supports a vast variety of animal and plant life. Some plant species can only be found in the Park and a seabird (Marbled Murrelet) nests in its old-growth conifers.

In some years one park species can add extra adrenaline to the race. This year Brett (my son) and I were counting down the miles to mile 4.0 of the Marathon. The R.D. had reported encounters with the beasts at that point of the 50K on Saturday. About 20 yards before mile 4.0 Brett saw what looked like a “cloud of dust” and shortly after that we heard agitated voices from the runners ahead.

In it for the full experience, we — and several other runners — plowed headlong into the cloud. The yellowjackets didn’t like that. A number of us were stung; some several times. The day before a runner in the 50K was stung 18 times.

Yellowjackets or not, running the Skyline to the Sea Marathon was like running a 26 mile nature trail and one of the finest courses I’ve done.

Many thanks to R.D. Greg Lanctot and Team PCTR and all the volunteers that helped with the event. For all the results and more info see the Ultrasignup event page, PCTR’s web site and Facebook page.

Here are a few photos taken along the way. Mileages specified are from my fenix 3 and are approximate.