The prominent ridge extending southeast from Twin Peaks to “Triplet Rocks” can be seen from many points of the Angeles high country. So named because of the triplet of sculpted white granitic monoliths at its summit, the isolated formation is generally considered to be the hardest to reach summit in the San Gabriel Mountains.

Here’s a view of “Triplet” ridge from a run up to Pleasant View Ridge a couple of weeks ago. In the photo Triplet Rocks is the rocky peaklet on the left end of the ridge and Twin Peaks (East) is on the far right. Peak 6834 is the prominent square-topped formation a little left of the midpoint of the ridge.

Today’s loosely formulated plan was to run/hike to the summit of Twin Peaks (east) and then see how far I could get out on the ridge in a reasonable amount of time. At the start of the run I had no idea what a “reasonable amount of time” would be.

It took me about a hour and fifty minutes to reach the east summit of Twin Peaks. On the way there I realized that I should have taken a couple extra bottles of water to stash on the summit. The roughly 60 oz. of water left in my pack wasn’t going to get me very far. I figured I could go about an hour down the ridge and still have enough water to get back and have a little in reserve. The day was windy and dry, but relatively cool. If necessary I could get water at a small spring on the Twin Peaks Trail on the way back.

How far did I make it? In an hour of hiking, scrambling, bouldering, bushwhacking and challenging route-finding, I made it to a rocky ledge below peak 7120+ and a little before the notch at peak 6834. I guessed it would have taken another 45 minutes to get to the summit of peak 6834. Next time — this wasn’t a place to push it!

I now have a much better idea of what’s going to be required to get to peak 6834 and Triplet Rocks. The north side of the ridge tends to be steep, loose, and at times very eroded. The south side of the ridge tends to be choked with scrub oaks and brush. On the way out I dropped down on the steep north slopes a couple of times; on the way back I tried some improbable lines through brush that (surprisingly) worked out and allowed me to stay more on the crest of the ridge.

It was an unusually busy day on Twin Peaks. On my way down from the peak I encountered several large groups of hikers. When I got back down to the car two tour buses were parked at the trailhead, their drivers patiently waiting for their patrons. Round trip the adventure had taken almost exactly six hours.

Notes:

In the fall of 2010 an experienced hiker doing this ridge became disoriented in rain, snow and whiteout conditions and was reported overdue. Following an air and ground search he was located on the ridge and airlifted to safety. He had notified a relative of his planned route and must have had most of what he needed to get by for the two nights and three days he was out. According to news reports he was in good enough shape to drive home following the rescue.

In April 2021 a hiker who became lost in the Mt. Waterman – Twin Peaks area was found on “Triplet” ridge after spending the night out. The hiker was located with the help of mapping enthusiast who used a photo taken by the hiker to narrow down his location. The area where he was found was within the Bobcat Fire burn area, and was closed at the time .

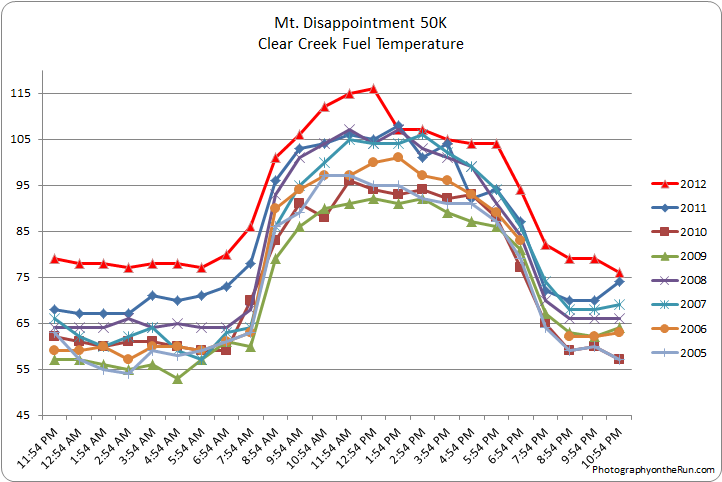

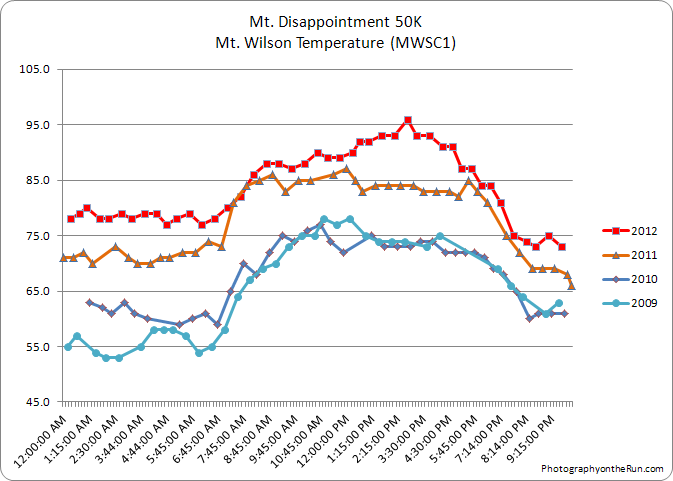

This was my eighth Mt. Disappointment 50K and by far the hottest and most difficult. How difficult? This year’s middle-of-the-pack time — the median time for all the finishers — was 8 hours 30 minutes. This was nearly 45 minutes longer than the median time in 2011, and 90 minutes longer than in 2006.

This was my eighth Mt. Disappointment 50K and by far the hottest and most difficult. How difficult? This year’s middle-of-the-pack time — the median time for all the finishers — was 8 hours 30 minutes. This was nearly 45 minutes longer than the median time in 2011, and 90 minutes longer than in 2006.