The photo above — of Josephine Peak — is the reciprocal view of this photo of Strawberry Peak. The photo of Strawberry from Josephine shows the dogleg approach along the ridge that connects Josephine Saddle to the northwest ridge of Strawberry Peak.

Strawberry has always been popular, but because of the Pandemic and fire closures, there has been an increase in the number of people doing the peak. Not having done the peak for a couple of years, I was curious to see if the condition of the use trail on Strawberry’s northwest ridge had changed.

Given my early start, I was surprised to find the small parking area for the Colby Canyon Trail nearly full. I don’t know where all those people went, because I passed only one small group on the way to Josephine Saddle, and I didn’t see anyone between Josephine Saddle and the summit. There was a group on the summit, but they had hiked the trail from Red Box.

The last time I did the loop over Strawberry was April 2019. At that time sections of the use trail along the ridge leading to the upper northwest ridge of Strawberry were badly overgrown. This time around, increased usage has generally improved the path along the approach ridge. Plus, there has been some work done on the section of trail that was the most overgrown. However, to benefit, you have to stay on the trail. It wanders all over the place, and if you get impatient, you’ll be fighting your way through thick, thorny brush.

There was a little patchy snow on the steep, deeply shaded, north face of the peak. The snow was generally left of the normal rock climbing route up the northwest ridge. The patch or two on the route were easily avoided. Early or late season, this more technical section can be like a deep freezer. Today, it was cool, but comfortable. As mentioned in other posts, the steep, upper part of Strawberry’s northwest ridge requires good route-finding and some rock climbing skill. It is important to stay on route.

The steep section of the ridge ends a little below the top of Strawberry. I paused there for a moment to enjoy the view… Was that music I heard coming from the summit?

It was. The group that was on the summit was kind of encamped there. It looked like they might be a while, so I just said hi, and started down the east side of the peak.

I expected a lot of people to be on the trail up Strawberry from Red Box. It was busy, but seemed about normal for a Sunday in Spring with idyllic weather. There were fewer large groups coming up from Red Box than in April 2019.

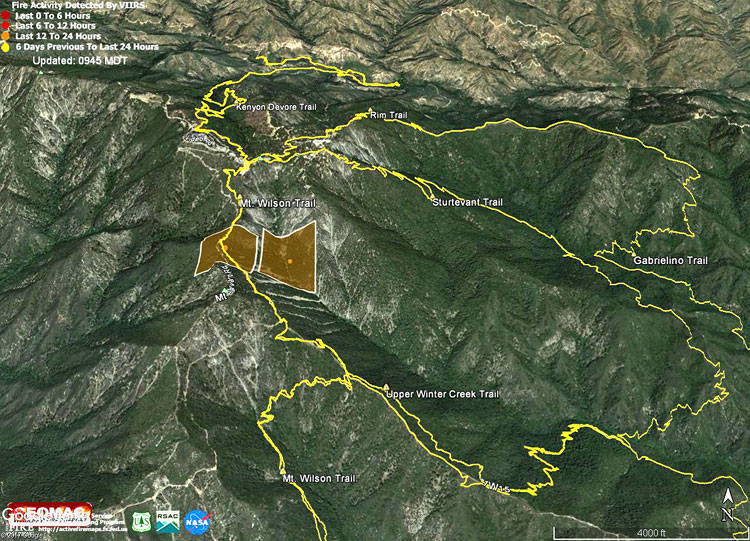

At Red Box I stopped to take a look at how the 2020 Bobcat Fire had impacted the upper part of the West Fork drainage. There was a substantial fire scar on the left side of the canyon, but the right side of the canyon looked better than I expected. An upcoming post will include an interactive 3D visualization of the Soil Burn Severity in the Bobcat Fire area, along with the GPS tracks of some popular trails.

For the first time in a long time, I didn’t encounter any mountain bikers on the Gabrielino Trail between Red Box and Switzer’s. There were plenty of tire tracks, so I must have been between groups. I did encounter two misplaced hikers. They stopped me and asked how much farther it was to the falls. Unfortunately, they had gone the wrong direction on the trail from Switzer’s, and were several miles from Switzer Falls.

At Switzer’s, I chugged up the access road to Hwy 2, and then ran on the verge next to road back to the Colby Trailhead. Somehow, more cars were packed into the small parking area.

Starting and ending at the Colby Trailhead, the loop is a little over 12 miles with about 3200′ of elevation gain/loss. Starting at Clear Creek adds about a mile to the loop. Some prefer to do it as keyhole loop, returning to Josephine Saddle from Lawlor Saddle using the Strawberry and Colby Trails. I haven’t done it that way, but the mileage looks to be only slightly less than the full loop through Red Box.

Some related posts: Strawberry Peak